The morning of October the 25th, 2023 seemed to be the dawn of another perfect day in the blissful, bustling resort city of Acapulco, Mexico. The palm trees rustled softly, the placid waves of the Pacific Ocean lapped up the beach with joy, and next to nobody who called this sprawling vacation metropolis their home would’ve suspected this serenity of coastal Paradise to be ripped apart anytime in the near future. The weatherman said a little tropical storm—Otis, was that the name?—may bring a blustery downpour later that night. But Otis was nothing to be concerned about—after all, Acapulco was rarely struck by Hurricanes.

This is the terrible and captivating story of one of the greatest forecasting blunders in modern meteorological history; the story of a Hurricane that defied all odds by orders of cyclonic magnitude; the story of a city, laid to ruin by the most powerful landfalling storm in Eastern Pacific history.

Unlike the season-long threat of landfalls in the Atlantic Basin you may be most familiar with, October in the East Pacific Basin (EPAC for short) is about the only month in this enigmatic basin where Hurricanes start getting cute and flirting with dangerous landfalls along the Mexican coast. During this time of the year, the climatological set-up becomes rather cheeky, steering organized tropical cyclones in semi-circle-like tracks that can put the west coast of the country in the crosshairs. And in the red-hot tropical Pacific, we are talking the crosshairs of some truly monstrous tropical cyclones, such as Hurricane Patricia (2015), and Hurricane Kenna (2002).

This may lead you to believe, then, that Mexico in the October EPAC must run right up there with the American Gulf Coast and the Philippines as the most tropically dangerous places in the world. Right?

While that can be a somewhat subjective opinion, there are a few reasons that Mexico typically doesn’t share the tropical VIP section with the above mentioned geographic locations. For one, having most of your landfalling tropical cyclones climatologically confined to October significantly limits the overall land impacts that can occur in the basin during any given year. Two, trough-induced wind shear—combined with the hellishly rough topography of Mexico’s coastline (which will rapidly cheese grate the precariously stacked convective levels of pristinely powerful Hurricanes)—almost always weaken storms well off of their peak intensity… before they’re able to drag themselves ashore. (Now… if said Hurricane’s peak intensity is “off the charts”—such as Patricia’s world-record 215 mph sustained winds, or Kenna’s not-to-be-minimized 165 mp—then Mexico could still be dealing with devastatingly strong storms bashing their way up the beach; even with historically rapid weakening, Patricia still made landfall as a strong Category 4 Hurricane, while Kenna held similar winds at 140 mph.) Thirdly—and possibly most importantly—the west coast of Mexico is not densely populated—few analogs to New Orleans and Tampa, Tacloban and Miami, Charleston and Bangladesh, can be found.

But there is one city, a very prodigious city, one whose name is synonymous with Paradise and pleasantries…

Acapulco, Guerrero.

A resort metropolis known for its high-rise beachfront hotels and gracious Coconut Palm trees. It’s the beautiful and luxurious heart of an apple whose skin is comprised of the mystically dangerous “cloud forests”: the wretched and mysterious mountains of Guerrero. They surround the city on nearly every side, guarding it from the encroaching and wild underbrush of Central America’s soggy, temperate rainforests. Within those tectonic walls of safety lies Acapulco itself, a city that makes its name on glassy facades, its reputation on stunning trypan seawater, and its money on wealthy and eager-to-disburse tourists (though American tourism has declined heavily in recent years, as Acapulco has the 10th highest murder rate of any city in the world). Encasing the city’s downtown core is Acapulco’s hypanthium: vast suburban centers that crawl up the mountainsides and pack the municipal population to over a million residents. It’s the largest port city in all of Mexico.

So, you’d think then, that with all that life and property pressed right up against the coast, in an area where the water is warm and the Coriolis effect has sufficient distance from the equator, that Acapulco would surely be ready for any Hurricane that may come their way?

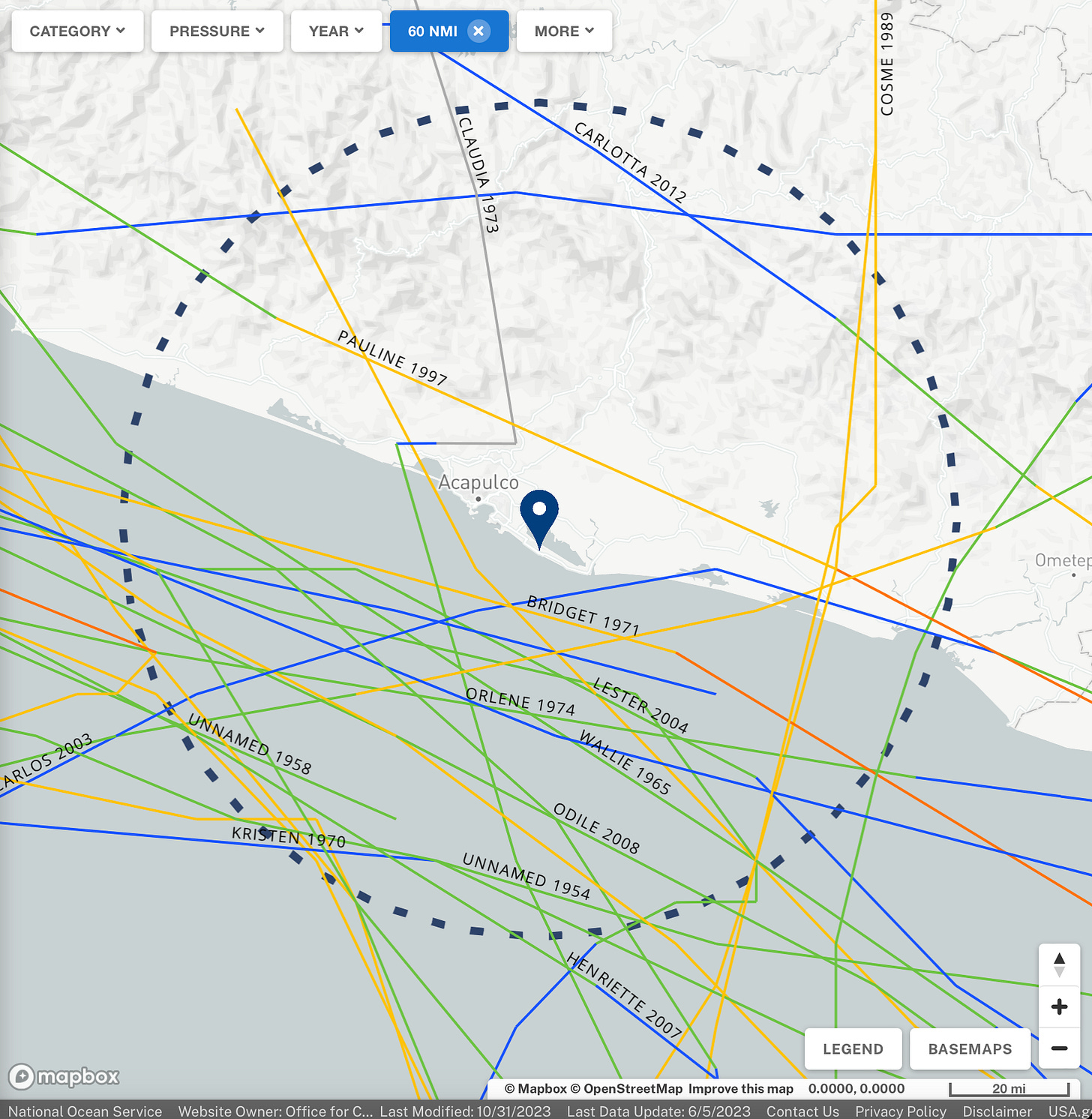

Counterintuitively, Acapulco had no preparations, and for no other basis than they had no reason to fear Major Hurricane landfalls. Just take a look for yourself:

On this map of all known Hurricane tracks within a 60 nautical mile radius of Acapulco, we find that just 1 can even be said to have had a direct-ish landfall over the city: an unnamed 85 mph Category 1 in June of 1951. Outside of this, only 2 other spinners have come even remotely close to directly impacting Acapulco: Bridget in 1971, who caused severe wind and rain damage in the city, and Pauline in 1997—but there’s much more to the story with her.

Despite the very low frequency of Hurricanes in Acapulco’s sphere of influence, the city was not completely nubile to past tropical catastrophes…

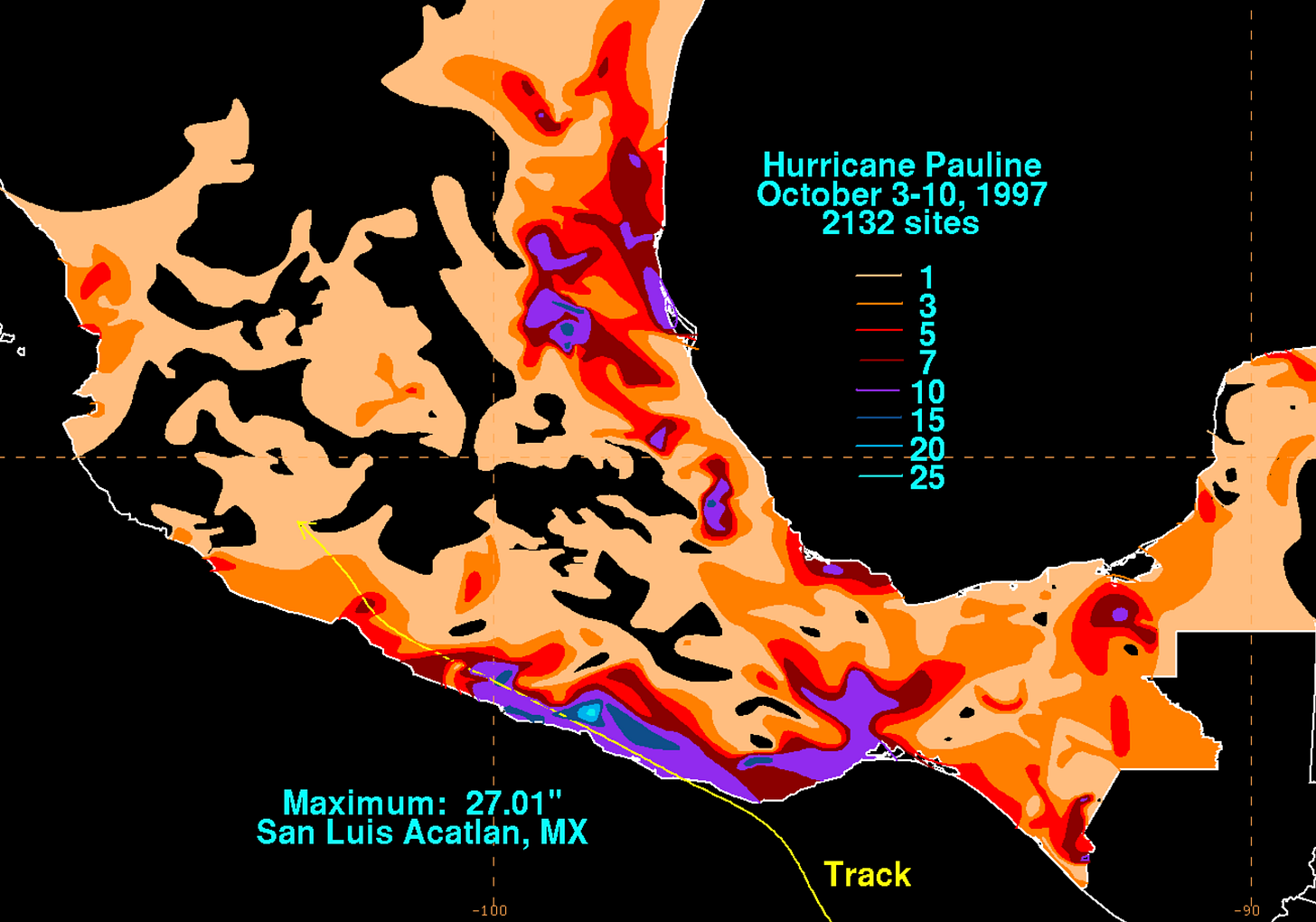

Hurricane Pauline, a compact Category 4 twirler at her peak, was a true natural disaster for the people of southwest Mexico. After her initial tantrum at landfall as a 110 mph Category 2, Pauline slithered begrudgingly down the coastline with disastrous consequences, dumping widespread rainfall totals of 15+ inches, with peak recordings of ~27 and ~32 inches, at San Luis Acatlan and Paso de Ovejas, respectively. The flooding that ensued was horrific, drowning anywhere from 230 to 2,300 people in the region. Acapulco and its surrounding fiefdom was the hardest hit—in just 24 hours, Pauline unwelcomely splashed ~17 inches over the city, cultivating and triggering fatal, sudden mudslides in that mountainous, suburban hypanthium. Homes were swept away; entire families disappeared; whole neighborhoods, buried in the thick, viscous consequence of Pauline’s crying tears of agony as she was torn apart by the Mexican mountains. She is, at minimum, the sixth deadliest Pacific Hurricane on record.

But think about how this happened—Pauline was a crawler, writhing and wringing out the incredible moisture contained in her circulation. She did her deeds on the principle of water, not wind, which left that metropolitan heart of Acapulco much less at risk when compared to the mountainous hypanthium that encases it. And as long as you weren’t among the unlucky propped up on the faces of the slippery mountainsides, odds were, that true and complete destruction would not be coming your way. After the storm had passed, there was no reason to start rethinking if Acapulco’s building codes should be able to withstand wind gusts higher than ~90 mph (a Category 1-equivalent); no reason to believe that any Hurricane of Pauline’s strength so far to the south was going to happen again anytime soon. Even Pauline herself precipitously weakened from 135 to 110 mph in just the final hours before landfall near Puerto Angel; courtesy of the coarse topography, which continued to faithfully subside any powerful Hurricane that dared approach it. So the bodies were counted, the pieces picked up, and Pauline written down as a southern Mexico one-off.

Acapulco remained completely naked to the Eastern Pacific.

Here comes Otis (and nobody cares)…

The National Hurricane Center released their first advisory on Tropical Depression 18E on Sunday, October 22nd—a wholly unremarkable cluster of lazily meandering thunderstorms that failed to waver even the glassy glide of the Manta Rays beneath the waves. 15 hours later, 18E metamorphosed into Tropical Storm Otis, but little had changed since the initial advisory, and the upgrade seemed mostly semantical. Little was expected of Otis going forward as well; his expectations were anything but great, and his ambitions were underwhelming. Forecast models vehemently insisted he didn’t have the will, the ambition to make anything of himself past a tiny, self-deprecatingly modest Category 1—at most. Many algorithms predicted even less organization for Otis by the time he approached Mexico’s coastline—many kept him under the 74 mph threshold by landfall in the country. Others didn’t even predict a landfall at all.

It wasn’t until the 4 am CDT National Hurricane Center advisory on October 23rd, that certainty began to narrow down a landfall in southwestern Mexico. By that time, the Mexican government had issued a Tropical Storm Watch for a 200+ mile stretch of coastline between the towns of Lagunas de Chacahua and Tecpan de Galeana; Acapulco lies approximately 55 miles to the southeast of the latter, putting the city in the northernmost quarter of the advised area. In the Hurricane Center’s bulletin, Otis was anticipated to undergo “some gradual strengthening” before making landfall late Tuesday into early Wednesday, October 24-25, respectively. At this time, Otis was partially spinning with humdrum 45 mph winds and a scarcely distinguishable 1,002 millibar central core, moving northward very slowly at less than 4-6 mph.

Up to this time increment, the young Otis had been having a rough time dealing with some of the common ailments that newborn tropical storms usually face. In spite of abundantly warm sea surface temperatures (SSTs), thoroughly and embracingly moist atmospheric layers, and favorable conditions for rising thunderstorm columns, Otis’ premature circulation was being sand scrubbed by moderate southeasterly vertical wind shear, delaying the system’s organization in the method of convective displacement. This meant that Otis was struggling mightily with getting those blossoming thunderstorms to stack and align correctly with the low level pressure circulation near the core, resulting in an open “eye” without protection, that was unable to stimulate further organization and/or meaningful intensification. So far, the models seemed to have been spot on with their predicted analysis of how Otis would fare in face of such hardship.

As we entered the afternoon hours of October the 23rd, convection was gradually fighting off the lightening wind shear, crawling closer to Otis’ still-exposed central core. This prompted the National Hurricane Center to update their forecast intensity; and by Advisory 7, it was anticipated that Otis would be near or at Category 1 intensity by landfall in Mexico. Forward motion began to shift slightly as well, toddling the storm towards the northwest vector compared to the due northward movement previously.

Overall, however, nothing unexpected seemed imminently apparent—Otis was still a nothingburger; a chopped tropical liver; a shrimpy little storm that would come and go and have nothing left to his name for the next six years. Nobody paid him attention—nobody cared he existed. It was at this time that most in the weather community—myself included—were preoccupied in tracking the clockwise-twirling Cyclone Lola in the South Pacific, and the heavy flooding ensuing in Yemen from Cyclone Tej. The unimpressive and unambitious tropical storm in the EPAC that will make landfall as a minimal Hurricane in, in all likelihood, a rural patch of western Mexico, understandably did not gleam with a suspiciously alluring shine to catch the eyes of media outlets and forecasters.

But that was about to change.

24 Hours to Landfall—Something’s Brewing Beneath the Clouds.

We will never know exactly what it was like to have been bobbing along the cobalt waves of the Pacific during the overnight hours of October 24th, inside the stormy, mystifying soup that was Tropical Storm Otis. But imagine, for a moment, that you are. Imagine, the dark growling of the water; the whistling of the wind that sprayed arcs of curling seawater off the tips of the cresting waves; the cold, swirling mushrooms of boiling thunderstorms, blossoming upwards, pining to become as frigidly powerful as possible. Inside the wet bowels of Otis, in the dead of night’s darkness, something strange was happening. It started small: a few, unorganized rainbands curling under the intimidating pressure of low-level vorticity. These semi-circles of intense thunderstorms slowly began to join hands, feeding off each other’s energy, somehow beating the wind shear that so endeavored to torture them.

From above, to the superficial eye, Otis looked no different than exactly what he was supposed to look like. Thunderstorm convection, as highlighted by infrared satellite imagery, remained highly sheared and displaced off the center of circulation. But when microwave imagery scanned the system’s core, penetrating through the cloudy convection and hazy water vapor, those peculiar little rainbands suddenly became visible to us outside observers—and they were far more organized around Otis’ center than anticipated.

But how was this possible? What had happened to the moderate wind shear that was supposed to consistently disrupt Otis’ tiny circulation and hold him down below a ~90 mph Cat 1?

The southeasterly shear had gone nowhere—it was, in fact, Otis who had done the dancing. As he was goaded into the northwest slant, Otis also accelerated unexpectedly, nearly doubling his forward speed to 7-10 mph. This faster, parallel motion suddenly hampered the shear’s dexterity to displace Otis’ convective layers, subtly allowing the tropical storm’s internal rainbands to commence central wrapping.

But another change came about in the upper-levels; a new wind that breathed new life into Otis’ unsuspecting banding patterns. As the storm travelled north, he began to intimately interact with a southern dip in the jet stream. This interaction, manifesting itself as a powerful, diverging belt of fast-flowing air known as a jet streak, grabbed Otis by his reins and spurred him into action. The jet was a euphoric drug for Otis, injecting him with the most powerful of all Hurricane stimulants: fresh, moist, oceanic air. The key word is fresh; these storms, they are strengthened, emboldened, invigorated by the cleanliness of the air that feeds them. They abhor dry smog and stale water vapor—for them, it’s uninspiring, and lacking the heat energy they absolutely crave. And in Otis’ case, he hit the jackpot at the end of the jet stream rainbow. The jet pulled at the storm’s outflow bands like a bitter old man yanking at the starter cord of his 15 year old lawn mower, ventilating Otis with alarming efficiency; but Otis was still a tropical storm, still assembling his primitive internal dynamics, and the effects of the jet streak were thus yet to effectively kick in.

It wasn’t until 1 pm CDT on October 24th when the first heads started to turn. In an intermediate advisory, the National Hurricane Center upgraded the system’s maximum sustained winds to 80 mph—officially making Otis a Category 1 Hurricane 12 hours ahead of schedule. Hurricane Warnings were now up for nearly the entire length of Guerrero’s coastline, and preparations were urged to be rushed to completion. But word was still slow to spread; and as for Acapulco’s residents, they were as aware of the Hurricane Otis as they were the Tropical Storm Otis.

Nevertheless, even in the circles of weather enthusiasts and laser-eyed meteorologists, the true, genuine alarm was yet to sink in. For one, the latest forecast cones consistently held Otis as a beach-scraper, paralleling him with the coastline and missing a direct hit on Acapulco to the west; and secondly, Otis had just a little over 12 hours before crossing over land—in reality, it was likely to be even less than that, as almost every storm that historically made landfall on Mexico’s west coast began weakening rapidly long before the eye itself crossed the beach (remember Hurricane Pauline?) due to land interaction from the venomous bite of the dry, rugged mountain ranges. Certainly, Otis had undergone a remarkably rapid and unexpected bout of organization that guaranteed he be at least a formidable storm by landfall; but with such little time left, there was surely no cause to sound the truly panicked alarm bells yet…

Little did we know, it was already too late.

12 Hours to Landfall—The Tempest Calls Our Bluff.

Shortly following the NHC’s dramatic upgrade of Otis into a Category 1 Hurricane at 1 pm CDT (which was based almost entirely upon satellite analysis), an Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunter mission entered the storm to provide advanced data of the environment inside. These flights are commonplace in the Atlantic Basin but much rarer for Eastern Pacific Hurricanes, due to the rarity of significant landfalling storms in the basin, as well as the low population density of these potentially affected areas. It wasn’t certain what the flight’s data logs would reveal, but viewing Otis’ aesthetics from the outside, he shouldn’t have been more than ~10 mph stronger than what satellite analysis suggested.

But when the data filed back, the results were unreservedly stunning.

Beyond all forecasts, beyond all reasonably conceived algorithmic predictions and projections, Hurricane Otis had tightened and intensified unbelievably quickly. The Hurricane Hunters had found that maximum sustained winds had already reached an astonishing 110 mph, 25 mph stronger than what the NHC had believed Otis to be based on the satellite estimates. The minimum central pressure was, too, a further 14 millibars more intense than the 985 number set just an hour earlier, signaling that it was no longer a shot in the dark if Otis was going to be a Major Hurricane by landfall.

The ultra-strong jet streak had fanned an incredible, blazing fire in the heart of Hurricane Otis; a fire so frenzied, so icily crazed, that it had taken him from a Tropical Storm to a near-Category 3 in just 4 hours. The replacement rate of the moist air that ventilated Otis’ arching outflow kicked its jingling spurs mercilessly into the convection embedded within the storm’s circulation, detonating the thunderstorm density in a raving, boiling blossom of lightning and wind and rain. A central dense overcast (CDO)—the thick, symmetrical core of convection that surrounds the eye of a Hurricane—was starting to consolidate and form multiple intense, vortical hot towers, thereby wrapping and urging the rapidly intensifying eyewall with a fervid, devoted passion. And this was all made possible thanks to Otis’ extremely small, compact size—with Hurricane-force winds extending only 30 miles across (that already had doubled from the 15 mile radius when Otis was first upgraded to Hurricane status), there was very little inertia stored in his youthful core, allowing the outflow jet to spin up his velocity with deadly quickness.

But even now, the realization was slow to set in—perhaps it was normalcy bias, seeing so many small storms like Otis intensify so fast, only to see them falter and die just as quickly. Because the great paradox of small tropical cyclones works much like a hallucinogen: it can bring you to a brief, ultra-energizing high of endless possibilities, only to crash you mercilessly back down to Earth with the force of a thousand hailstones just as forcefully, and abruptly. Many dozens of compact Hurricanes throughout meteorological history have gone through this, intensifying explosively quick, but going too fast for their own good, becoming too hungry for power and naive in not allowing their critical internal dynamics time to stack up properly; instead choosing to destroy them altogether when they’ve started spinning so fast that their entire being is rife with instability. Not only that, but small storms have finicky, walk-on-eggshell tempers: the slightest of imperfections in their surrounding environment can send them spinning in a dizzyingly destructive tantrum.

Having said that, Otis had already proven his emotional durability was that of an older, larger, and much wiser tropical cyclone—he did this by surpassing his wind shear nemesis, as highlighted earlier. So now, it was down to his internal dynamics. In particular, there was an immediate search for the latest microwave passes of Otis’ internal structure to see whether or not a secondary eyewall was beginning to coalesce. Almost always with small storms of his caliber, the eyewall replacement cycle is one of the first things to trigger the end of the rapid intensification phase, often doing so long before the initial eyewall is actually allowed to fulfill its full potential. But as the images of what the piercing eyes of microwave wavelengths can provide us came in, they showed yet another incredible, physical attribute displayed by Hurricane Otis: there was no secondary eyewall. Not even a hint of one; not even an echo. All that could be seen was the glaring, electric, exploding primary eyewall that was squeezing tighter and tighter around an increasingly well-defined pinhole eye in the bullseye of Otis’ whirling core.

It was only with the x-ray vision of the microwave scans, that this could this be seen. From space, Hurricane Otis was a perplexingly strong storm for a system that looked so heartily disorganized. The CDO was wobbly, incomplete; and the heaviest pools of convection were exclusively displaced, first in the Hurricane’s southern quadrant, and then the western. Otis’ eye was also unclear, visible only by the binary convective hot towers intermediately rotating around the storm’s center. The architecture beneath the clouds was superb; the facade on the outside was odd, globular, and dangerously deceiving.

The Hurricane Hunter mission was still underway by the time the 4 pm CDT complete advisory on Otis was released by the NHC; and what they experienced just during the duration of their flight within the storm was downright terrifying. Otis had officially become a red-blooded Major Hurricane, with sustained winds of 125 mph, and a pressure that had fallen another 11 millibars in 2 hours. Otis had jumped three Categories in as many advisories, and thus was single-handedly redefining rapid intensification, in his case to mean something different entirely: explosive intensification.

The combining factors of the core’s small size, the particularly steamy coastal water temperatures, and the powerful jet streak had transformed Otis into a bomb. He was a powder keg sitting on millions of barrels of tropical gunpower—and the fuse had already been more than lit, it had reached the point of no return, the point of a single flash that supercharged an unstoppable expanding cloud of heat energy and angular momentum. The bomb had made it past our security, slipped right underneath our noses and planted itself in our backyard, disguised further still by an inconspicuously messy bush of clustered thunderstorms that distracted and diverted.

Professional storm chasers around the country were as shocked as anybody, and perhaps even more so. They lived to intercept the cores of Major Hurricane just like Otis, but now they found themselves as helpless outside observers to the approaching storm in Guerrero. Not one of them had planned on meeting up with a meager Tropical Storm/minimal Cat 1 in the middle of southern Mexico—and now, there was quite literally no time left to travel there and record the now-imminent destruction that was methodically marching closer. With just 9 hours left until landfall (which now, very suddenly seemed like a terrifying eternity compared to earlier), the weather-watching-world could only hope to try and warn as many people in the faraway Mexican state as possible.

The situation was desperate—and with every hour that passed, with every new advisory that came in, with every millibar that dropped, the terrifying reality was becoming clearer and clearer: Hurricane Otis wasn’t going to stop until the devastating, bitter end…

And almost nobody in Acapulco had any idea he was coming.

6 Hours to Landfall—Acapulco in their Final Twilight.

7 pm CDT, October 24th, 2023—other than a black horizon and some choppy waves, the city of Acapulco rests in the darkening sky, tranquil, and content. The weather is expected to turn foul in the coming hours, as tonight is the night when the cheeky little Hurricane named Otis should be coming ashore to cause quite a blustery ruckus. Most are unthreatened by this tropical cyclone and the casual nature with which it has been reported on. They intend on riding out the worst of it in their homes and high-rise hotel rooms, not thinking much of the modest way with which Otis churns.

But 85 miles to the southeast, in the heart of the lion’s den, Hurricane Otis was smashing any modesty he had left with the violent pounding of a convective hammer. Within his fierce eyewall that is greedily ripping away at the warm, moist air of the Pacific Ocean’s surface, Otis is strengthening at neck-breaking speed. The 3 hours following the 4 pm CDT NHC advisory would turn out to be the storm’s single most incredible burst of intensification—20 mph gained in strength and a 19 millibar drop in central air pressure during that increment. Otis, despite still appearing relatively lopsided on satellite, was now a 145 mph Category 4 buzzsaw, and had more than doubled his maximum sustained winds in 9 hours over the course of that afternoon.

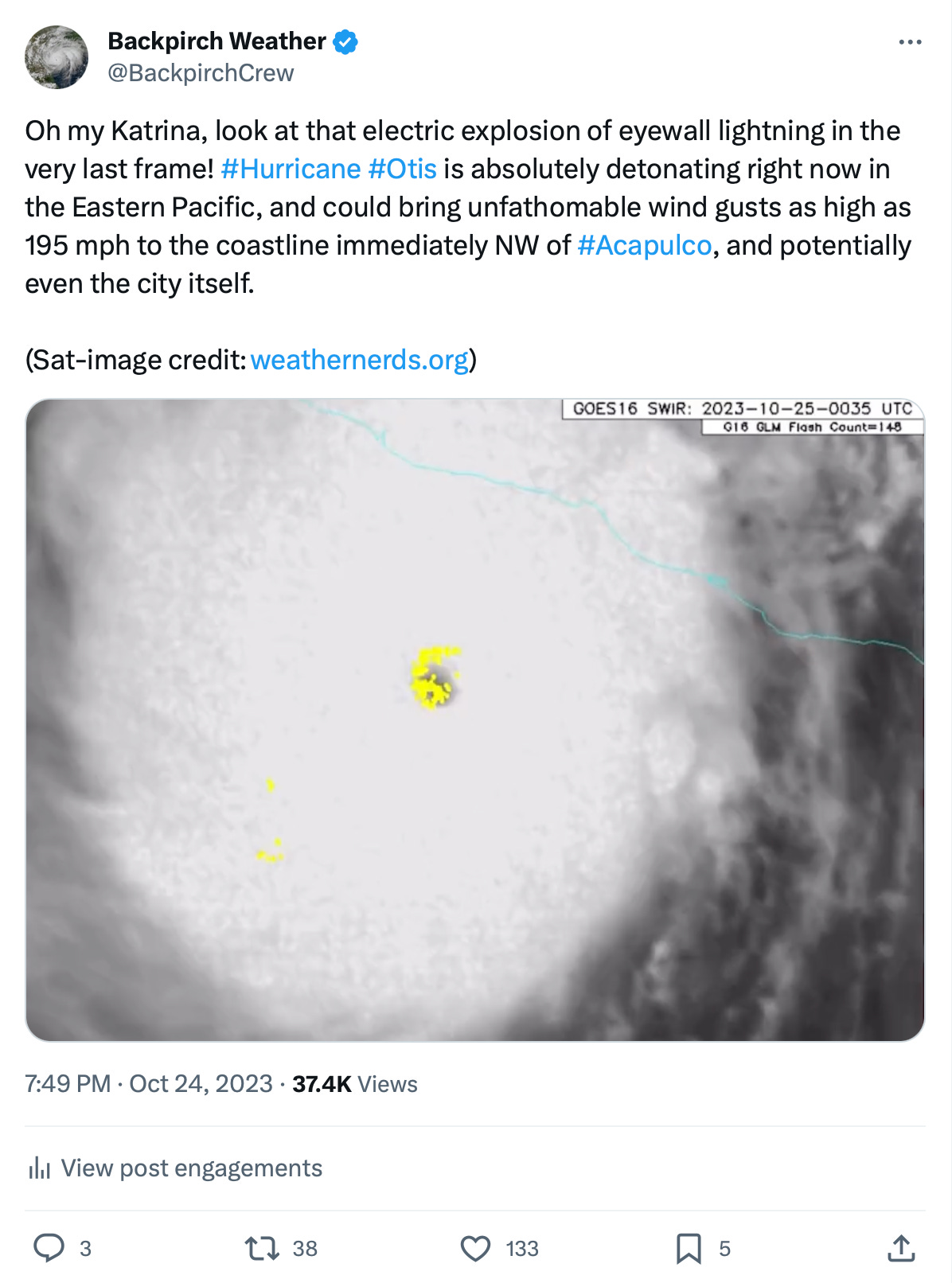

During this time, the lightning frequency and density inside Otis’ eyewall was absolutely exploding, displaying the hallmark sign for ongoing rapid intensification inside a rageful Major Hurricane, who’s thoroughly dissatisfied with his current ferocity.

As the forecast track for Otis quickly narrowed down towards Acapulco, and there were no signs—internally or externally—that Otis’ unbelievable rate of intensification was going to slow, dire warnings were desperately being communicated across social media. The NHC’s bulletins now contained grave, harrowing language, regarding Otis “to be a potentially catastrophic category 5 hurricane when the center reaches the coast”. On X/Twitter, people pleaded with friends and family whom were residents of Acapulco, telling them urgently to evacuate immediately; and if not evacuate, then to prepare and take cover as best as one could with the minuscule time remaining. But even now, many of the residents still were unaware of the catastrophe rolling down their road. Otis’ quickness was unprecedented, unpredicted, and unimaginable. He was challenging almost everything we thought we knew about the speed limit of rapid intensification for Hurricanes—but even more than that, he was straining the tedious trust we’d developed with forecast models from years of imperfect but steadily improving algorithmic development and execution. How had the models failed so utterly to see the conditions that Otis was swimming in were so conducive for rapid intensification? Let alone explosive intensification?

Attention turned to the specific geography of Acapulco itself, and where exactly the strongest vector of Otis’ winds, the northeastern quadrant of the eyewall, would strike shore. The concave curvature of Acapulco Bay, especially the hook of the Las Playas peninsula (famous for its steep La Quebrada ocean cliffs), looked like a potential nightmare scenario for catastrophic storm surge inundation. The infamous high-rise hotels were placed right up on the edge of the bay, along with the cluttered outcroppings of boat docks and yacht clubs. Behind the beach line, the vast majority of the city’s extremely dense, urban sector lie very close to sea-level elevation, presenting a possibly disastrous seawater flooding potential that would rage through the super-clustered homes and buildings. Moving out to the periphery of the city, well above sea-level atop the Guerrero mountains, people were under a completely different threat from Otis—the same threat that came to fruition in the only other two storms to affect the city, Bridget and Pauline. With both of those storms, rainfall-induced mudslides did the damage and the death amongst the rural and suburban neighborhoods of Acapulco.

This presented quite a dilemma for forecasters urgently warning residents to get away from the beach—for going up to the hills may be just as dangerous as any storm surge flooding that would incur in the low-lying areas. The inescapable threat, however, was Otis’ rapidly increasing winds—but even then, no one could’ve comprehended the horror they would inflict.

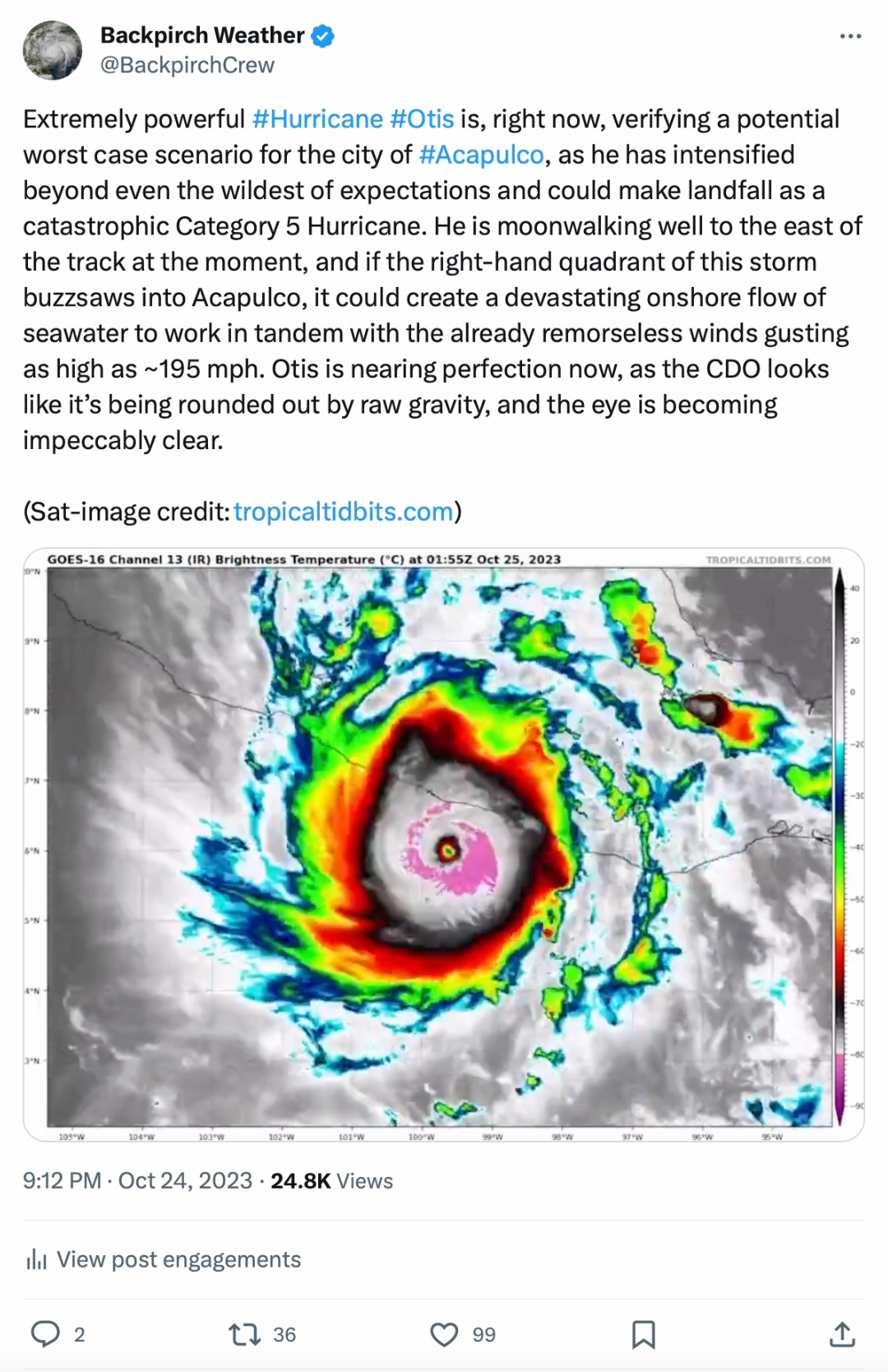

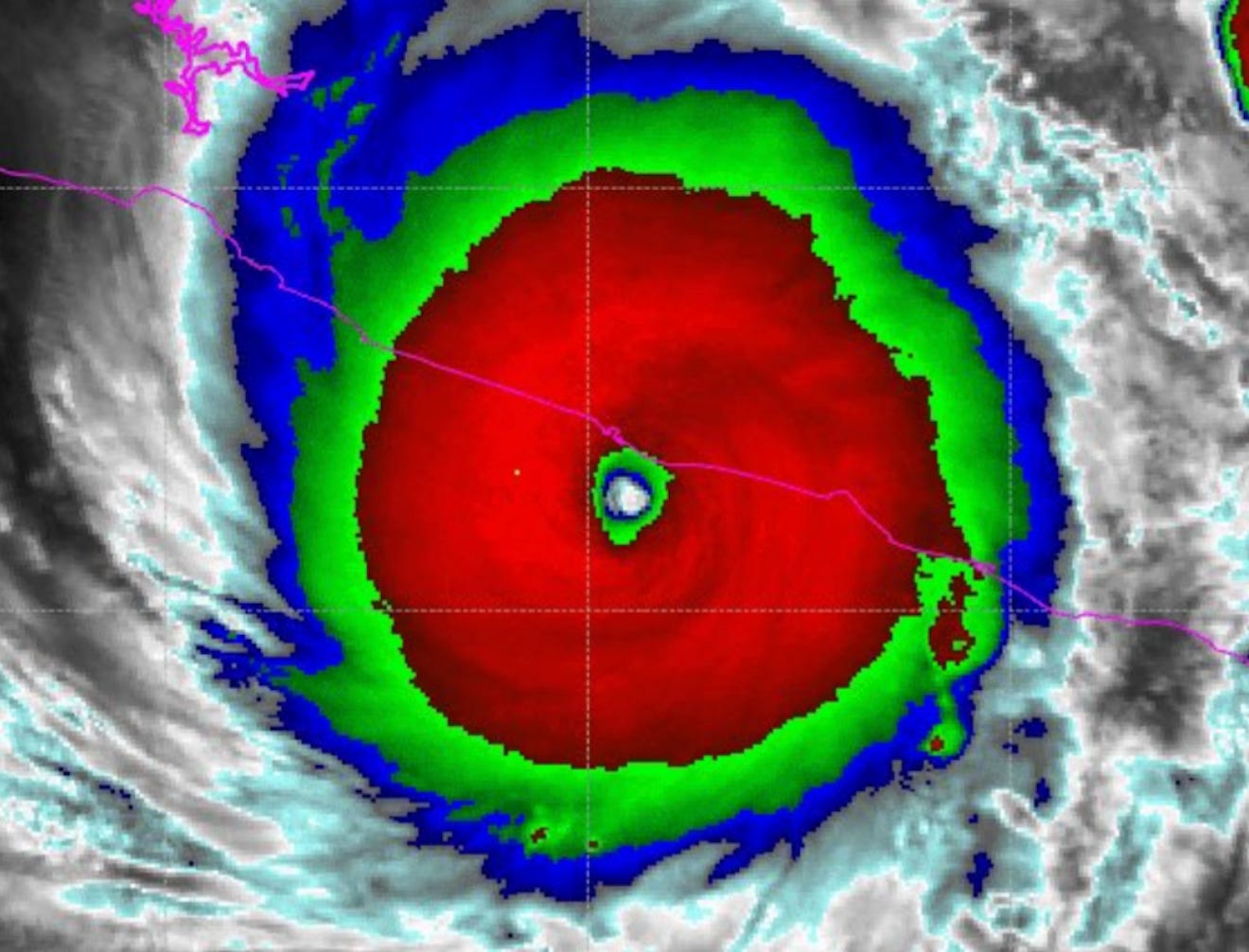

As the clock ticked forward to 9 pm CDT, the situation was only deteriorating faster. Hurricane Otis was organizing smoother than ever—in a single, lightning-fast flash, the persistently west-heavy CDO homogenized powerfully, as if another shot of adrenaline had been released into Otis’ veins. The core cloud tops coalesced in an angular, vortical explosion of gravity waves and heat energy, with wickedly glacial concentric convective rings as cold as -115 ℉ embedding their claws deeply around the voltaic eyewall. Simultaneously, Otis’ pinhole eye finally cleared out its clouds with a violent and sudden burst of hot, sinking air, blinking open with a diabolical gleam that glittered all the way down to the Pacific’s raucous surface.

Even more substantial was Otis’ direction of movement. With every satellite frame that updated, it became clear the center of the Hurricane was drifting well off to the east of the NHC’s forecast line. This drift continued until Otis was riding the very eastern edge of the overlayed cone of uncertainty—meaning that the storm’s eyewall would not skirt or miss Acapulco to the west, as previously predicted, but rather barrel straight into the city with the strongest quadrant of winds leading the way. This was not just grim in the fact that the core eyewall would be ripping straight through Acapulco, but it also meant that the direction of the winds would be pushing straight onshore, piling into Acapulco Bay and thereby increasing the potential storm surge savagery exponentially.

It was a true worst-case-scenario direction shift in Otis’ path.

48 minutes later, when the clock hand tipped over to 10 pm CDT, it seemed to do so in slow-motion. It felt as though days had been compressed into a 24 hour blur—a blur as fast as the swirling clouds within the unhinged cyclone.

In just the NHC’s 12th Advisory of the storm, Hurricane Otis jumped once again, increasing 15 mph and dropping his pressure another 14 millibars. He was now officially a compact Category 5 behemoth, raging with 160 mph winds and a core pressure of 927 mb.—just 55 miles south-southeast of Acapulco.

Forecasters and meteorologists around the world—becoming more and more helpless as time quickly ran out—now had to cope with the fact that a Category 5 eyewall was going to imminently crush a metropolitan city, whose 1+ million inhabitants had virtually no time to prepare nor evacuate from the path of the storm.

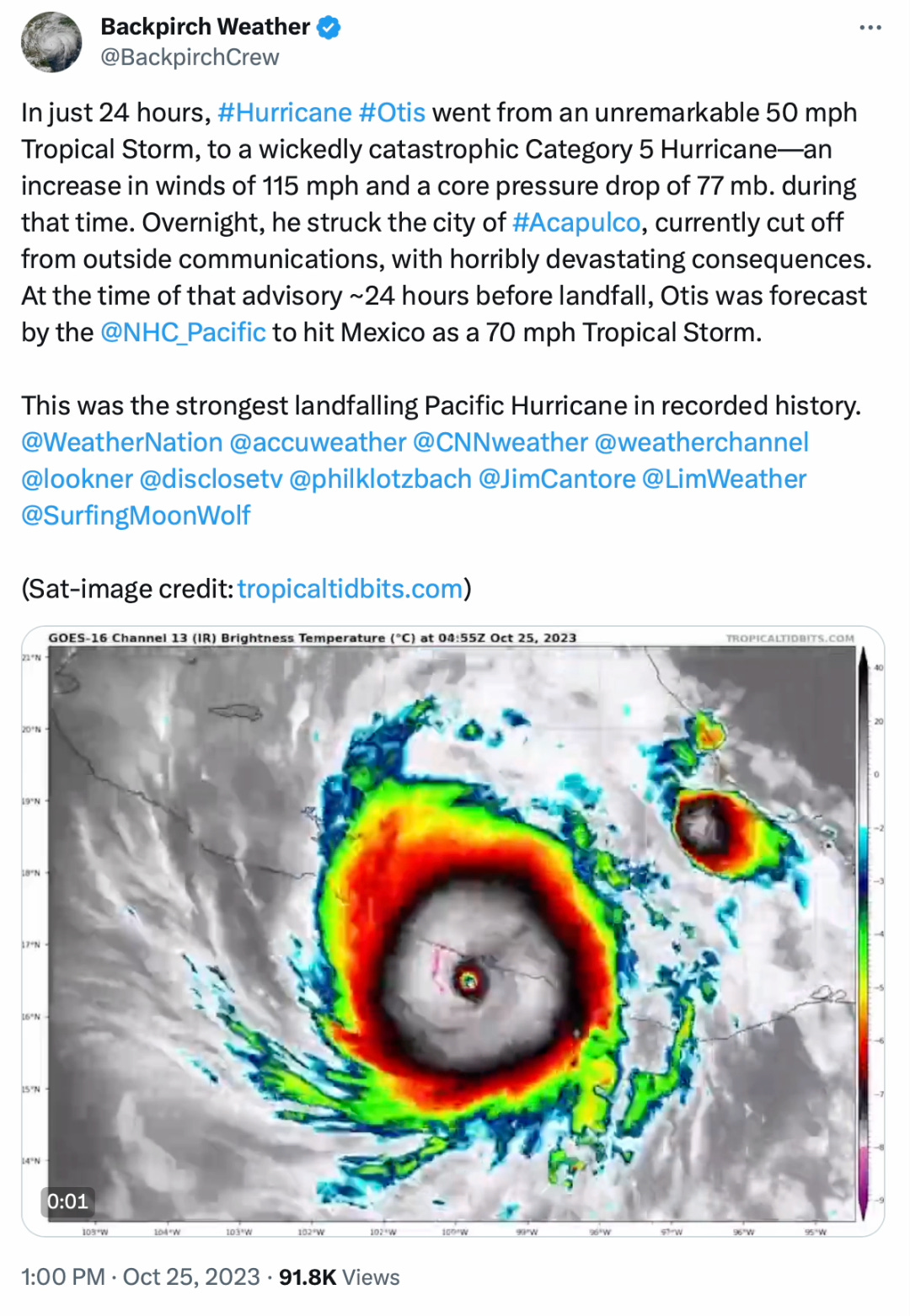

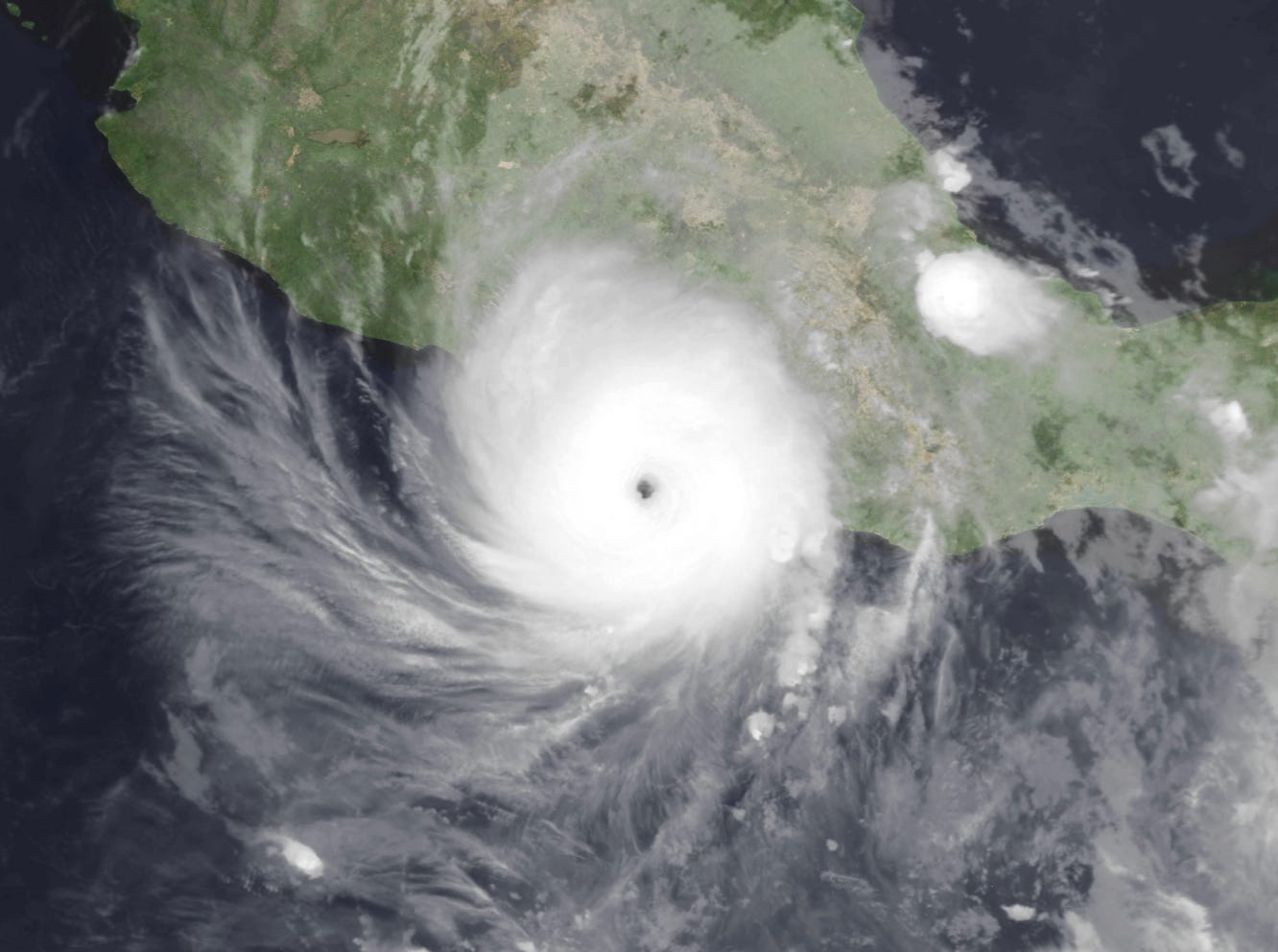

At 11 pm CDT, Hurricane Otis completed his final growth spurt, reaching what would be his peak intensity of 165 mph maximum sustained winds, and a forceful minimum pressure of 923 millibars (he would hold here through landfall), making him the strongest storm of the 2023 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season. Lightning intensity within the eyewall had reached a new crescendo, firing hotter and faster than ever before. By the time Otis was 45 miles from ground zero, Mexico’s mountains finally had begun to negatively interact with the storm—but it was far too late for Otis to weaken meaningfully.

The strongest landfalling Hurricane in Eastern Pacific history was just moments away from Acapulco’s heart.

The Clock Strikes Landfall.

"...EYE OF CATEGORY 5 HURRICANE OTIS ABOUT TO MAKE LANDFALL NEAR ACAPULCO MEXICO... ...CATASTROPHIC DAMAGE LIKELY WHERE THE CORE MOVES ONSHORE..." -National Hurricane Center, Forecaster Brown/Kelly at 1 AM CDT

The Clock rolls onward to October the 25th, and a new night begins—a night to be filled with horror. A night howling with the agonized scream of the winds and the terrorized wails of children. A night where the sounds of shattering glass and pounding waves were echoed phantoms in the dark, sadistic zephyrs of a Category 5’s ruthless eyewall.

The Acapulco International Airport is among the first areas to enter Otis’ core as he cuts sharply into the coastline from the southeast, tossing light aircraft like autumn leaves and gutting the air traffic control tower. The airport’s hangars crumple like tinfoil, and the runways themselves do everything they can to keep from peeling away.

The city of Acapulco itself was next on the chopping block. After being drenched with heavy precipitation by Otis’ CDO for the last several hours, the eyewall’s barbaric, unabated winds come off Acapulco Bay like a sea-sprayed hammer. It is a thick, suffocating blanket of purified heat energy, a toxic mixture of extreme rainfall and Pacific sea spray. This gray, misty wall of destructive temperament slams into the oceanside buildings of Acapulco harder than a freight train, inciting the city streets to tremble in fear. The storm has arrived to an unsuspecting populace, who are caught in the climax of tropical chaos.

Now, put yourself in Acapulco during that fateful night of October the 25th—imagine you were an amateur storm chaser who got lucky and saw Otis’ intensification ahead of time. You gather your equipment and head to Acapulco—you are staying in a hotel room, in one of the magnificent high-rises right on the beach and the bay. As the great storm approaches, the wind and rain lash angrily outside; curtains of frenzied, racing raindrops roar past the golden rays of the city’s lights. The palm fronds are twisted and yanked; the corners of the windows whistle like a freight train’s wheels screeching to a fiery halt atop metallic railroad tracks. You watch as Otis rages, in awe of his power, perhaps even fascinated of what he’s accomplished in such little time, the improbable odds he overcame to achieve such fury.

But new lights suddenly flash: an unbelievably bright, blue glow from somewhere in the distance flickers fiercely. Then the lights snap off; out your window, the landscape is plunged into darkness. The humming whir of the room’s air conditioning winds down; only the fanatical rain whipping against your window can be heard. Apprehension tenses your muscles as you realize you’re not actually in the worst of what Otis has to offer. Your reflection in the window becomes intermittently distorted as the glass flexes inward with the punch of every wrathful gust of over ~190 mph—suddenly, the howl begins to morph into a scream. And as the squealing gale increases, a breaking point is reached. The windows shatter—unbrokenly smooth panels instantaneously splintering into thousands of glittery, icy fragments. Otis growls, for his winds have wrestled loose from their chains and are free to penetrate the hotel room. You scramble for cover in the bathroom as the ceiling panels are soaked by rain and torn to the floor. Being a storm chaser, you’ve already experienced a few Hurricanes from the safety of an elevated hotel room—you never considered Otis could reach you here. You cover your ears, but you hear the insolence outside: glass is disintegrating all around the city, sounding like a faint, sickly sweet holiday jingle beneath the Halloween horror of the eyewall’s agonized screams.

Down on the streets, the wind thrashes with the force of catastrophe that only a true Category 5 eyewall can deliver. Metal, glass, palm fronds, and splintered vegetation fly as swarms of deadly projectiles, bouncing, clanging, and demolishing anything in their trajectory. Cars and vehicles, most of which were never thought to be moved due to the suddenness of Otis’ arrival, are smashed and wrecked in ways akin to what you’d usually only see from a powerful midwestern tornado. Feet of storm surge roll over the dunes and inundate the streets, filling ground floors and creating a horrible, noxious brown soup of mangled debris and toxic seawater.

Speeding up the mountains around Acapulco’s periphery, the hell is only exacerbated. Whole neighborhoods, constructed poorly and with no design intended to survive the sustained winds of a Major Hurricane, are shredded mercilessly. Roofs break off in flapping chunks, leaving nothing of ceilings except the prison bars of structural 2-by-4s. The rainforest’s trees snap like toothpicks, sending their branches cascading to the ground in a destructive flurry. Power poles and whole transmission towers are toppled like kids’ toys, completely cutting off Acapulco from the outside world. Isolated mudslides cascade down saturated slopes of brown sludge and hard rocks, burying whole homes downstream.

Despite the temperature in Otis’ eye cooling significantly during the final hour before landfall (caused by clouds imploding inwards from the eyewall), and the CDO losing its previously perfect convective symmetry, he managed to hold strong to his Category 5 peak until the very last second of his core’s time over the Pacific’s delicious waters ran out. Verifying this intensity was the historic recording of a weather station in Acapulco Bay, at 12:40 am CDT:

The station clocked a savage 204.9 mph rupture of wind, unofficially making this the 6th highest wind gust ever recorded on Earth, and the 4th highest to be produced by a tropical cyclone.

Hurricane Otis made landfall at 1:25 am CDT, October 25th, 2023, 5 miles immediately south of Acapulco, Mexico.

Conditions in the city were more extreme than ever as the eyewall’s unimaginable power raged harder and harder, knowing it was backed into a corner, and that its death was imminent. With gusts well over 200 mph, the expensive, glamorous facades and window-walls of the high-rise hotels were completely decimated. Otis shredded panels and shattered windows, tearing off the buildings’ skin and gutting their naked, exposed interior. They were sentinels to the city, and sacrificed themselves to the worst of the winds as they lined Acapulco Bay and had no protection from the gales that glided frictionless across the ocean surface.

The hotels’ dignity were stripped away cruelly and quickly, leaving them as pale, shivering, skeletons; a shell of the glory they used to behold. The carnage cleaned out whole rooms, making them open ladder steps littered with glass and building material. At the Princess Hotel, lying a few miles southeast of the city, storm surge rolling up the beach added a new equation of destruction, filling the lobby with entire vehicles as tattered pieces of the hotel itself were torn apart and rained down the shaft of the central atrium.

In Acapulco Bay’s hectic waters, multi-million dollar yachts were tossed and capsized effortlessly by Otis’ powerful and relentless army of Pacific waves; many drown trying to reach their boats in the height of the onslaught. In the mountains, entire swaths of forest are mowed down to a vegetative pulp, stripping away the lively greenery and leaving only the death of mud. Otis’ wind becomes so furious, so climactic, that not even the palm trees are able to withstand the butchery.

When the dark morning finally seems to progress—when Otis’ winds start to have cried their last—a light at the end of the tunnel glows. We come back to you in your hotel room: you creep out of the bathroom, peaking through the cracked door. Rain still spatters outside, but you sense the storm has finally passed after what seemed like a century of tortured screaming and pure slaughter. As you walk out across the floor, your shoes crunch the glass like icy snow beneath your feet. The entire room is soaked; the ceiling, torn. You cautiously tiptoe out to the edge of your balcony, and though it is still dark, you realize you are able to see inside the adjacent rooms left, right, above, and below you.

And now, you realize with a jolt, just how extensive Otis’ terror was. You cannot see through the blackness that has descended over Acapulco—but you can smell the destruction on the tired breeze, hear the unnerving silence of a city brought to its knees, and you fear what morning will unveil.

Acapulco’s Aftermath.

The Sun left Acapulco on October 25th as it had always been before: the bustling city of dazzling resorts, dashing weather, and an electrifying night life.

When she greeted the city again, it laid in cloudy ruins.

Nothing was dazzling, dashing, or electrifying on these devastated streets. As a sunshine that seemed paler than usual illuminated the ruins of Acapulco, city residents, turned survivors, shuffled numbly from their nooks of hiding and safety. The monster was gone, but his scent permeated the surface of everything he’d touched—everything he’d destroyed.

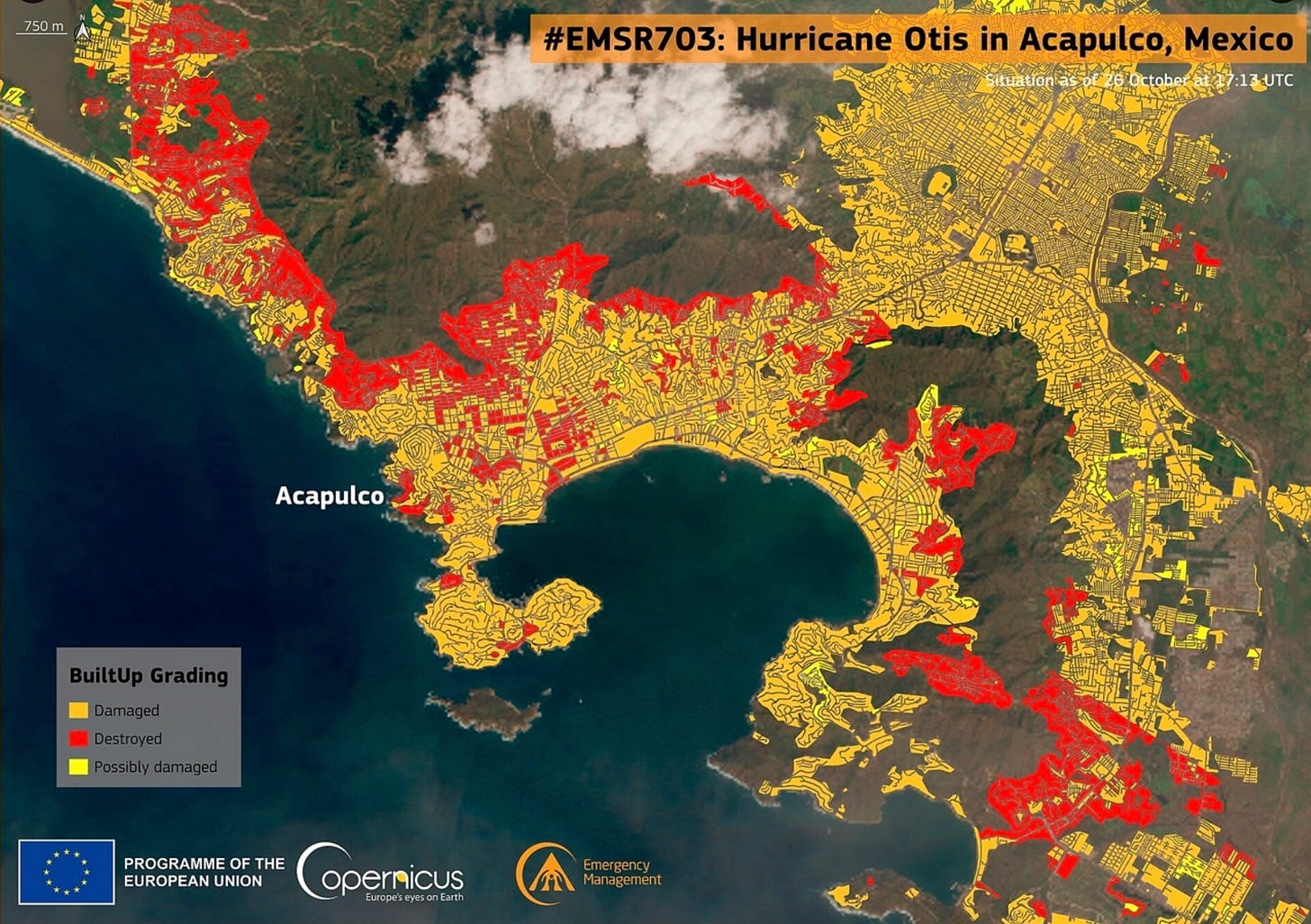

Not a single inch of the city went untouched. Twisted scrap metal, broken glass, wrecked vehicles, splintered lumber, demolished building debris, and endless piles of miscellaneous junk, cluttered whole streets. Dozens of luxury hotels, stripped and disemboweled; entire suburban neighborhoods, practically leveled. Hangars and gas stations, convenience stores and restaurants, completely laid to ruin. The scale of devastation was shocking.

Freshwater flooding, running off from the Guerrero mountains, worked in tandem with fallen trees, to effectively block all entrances and exits to the city. The mountains themselves had been shaved of their vegetation, as they faced even stronger winds aloft than at the surface. As daylight slowly revealed the extent of the damage, it became clear that apart from the coastal pulverization of the resort towers, Acapulco’s suburban perimeter was the hardest hit. The structures and homes making up the winding, mountainous neighborhoods weren’t constructed with a single thought related to withstanding Hurricane-force winds, and they suffered thorough, catastrophic damage.

In Major Hurricane landfalls, it’s rare to see this situation of more complete destruction further away from the immediate coast, because as devastating as Category 5 winds are, it’s almost always the coastal storm surge that causes the most complete destruction. But in Otis’ case, it was the reverse: the vast majority of the damage in Acapulco was inflicted purely by wind, rather than storm surge. Several factors contributed to this: first, Otis was a small, compact storm, his eyewall stretching only 30 miles across. Second was Otis’ time over water—because of the explosive, last minute intensification, the system had just ~15 hours over water at Hurricane strength, giving Otis no time to whip the ocean beneath him into a volumetric frenzy and push water over the beach. Third was the coastal geography of Pacific Mexico, which featured both a steep continental shelf and very dense coral structures (this would act much like a mangrove swamp on the Gulf Coast, acting to dampen the ferocity of the oncoming waves).

These factors combined to limit Otis’ surge well under what you’d normally expect from a landfalling Category 5 Hurricane, and keeping the waves atop the surge much more subdued.

The concentration of complete ruination increased in the densely packed neighborhoods of Jardin and San Isidro, on Acapulco’s northwestern quadrant. Mudslides ravaged the very hilly topography, creating an apocalyptic hellscape that went on forever in every direction.

The entirety of the Paso Limonero region suffered extensive damage as well, but was spared from much of the additional mudslide sledgehammer that absolutely smashed hundreds of homes in the mountains.

Back to the city’s hotel section along Acapulco Bay, stunning footage from helicopter flights soon exposed to view the staggering magnitude of Otis’ devastation:

To sum up, Hurricane Otis has been tallied for at least $11.5 billion dollars in damage to the city of Acapulco—a likely conservative estimate—soundly making him the costliest EPAC Hurricane ever recorded.

In the days following landfall, expansive and violent looting bloomed across the ruined city like clusters of poisonous mushrooms after a chilly downpour, prompting the Mexican government to deploy national guard troops in the area.

Potable water and food very quickly became major issues in the localized humanitarian crisis. On October 28th, three days after landfall, the Mexican government managed to ship in 2,100 gallons of food and 4,200 gallons of clean drinking water to the more than 220,000 displaced residents of Acapulco. By November 1st, the amount had accumulated to 420,000 gallons of water shipped in, and a total of 145,000 food rations distributed (including over 80,000 pounds of tortillas).

The official death toll followed the recent trend of controversial casualty tallies from tropical cyclone landfalls in non-U.S. countries, but local residents have reported it to be as high as >120 individuals. Official statistics place the tally at 48 at the writing of this newsletter—43 of which reportedly died in the municipality of Coyuca de Benitez alone, where the neighborhoods of San Isidro are located northwest of the city’s urban center—with another 58 unaccounted for. We may be a long time away from knowing the true death toll inflicted by Hurricane Otis, if ever. As mentioned above, the official numbers will very likely be underestimates of the reality.

Undoubtedly, had forecast models foreseen the conditions Otis wandered into, and had the intensification rate been less extreme, many would not have perished from being caught so off-guard by the storm’s historic leap from an irrelevant tropical storm to a Category 5 buzzsaw in just 12 hours.

Ultimately, the complete and utter failure for any weather models or meteorological agencies to foresee Otis’ incredibly rapid intensification, led to one of the most consequential disasters in modern forecasting history.

For the first time since Hurricane Andrew’s landfall in Miami, Florida in August of 1992, we got a taste of what it looks like when a Category 5 eyewall cuts through a densely-populated, urban municipality. The location, angle, and timing of landfall could not have produced a worse outcome for Acapulco and its residents—an unvarnished, nightmare scenario.

The numerous records Otis set will be carved in the stone pages of meteorological history as a testament to how little we truly know about the phenomenon of rapid intensification. The horrors and sensations of a Category 5’s honesty will be etched into the minds of the hundreds of thousands of survivors forever—and the serene seduction of calmness, never to be unnaturally presumed again.

It’s November the 13th, 2023, in the city of Acapulco, Mexico. The palm trees, they rustle softly; the Pacific Ocean, she laps quietly up the beach with joy. The morning shines with bliss—but next to nobody here feels the same. The sprawling vacation metropolis is now a derelict, tumbledown nightmare, ripped apart and tossed into the infernal wind without mercy or courtesy.

The weatherman had said a little tropical storm was coming… I suppose that little tropical storm must’ve heard him.