The Coriolis Clock-Episode III

Camagüey Shores

This piece uses both real, historical footage/photos and AI generated images. This was done due to the substantial lack of photographs in and around Santa Cruz del Sur, Cuba in 1932, and in hopes of painting a more vivid picture of what the damage from the 1932 “Cuba” Hurricane would have looked like. All images that are AI generated will be delineated as such. No writing material in this piece has been produced by AI. It is and always will be written by myself, the author.

The tiny town of Santa Cruz del Sur had never done anything to anyone—never imposed itself too sharply on the environment, never encroached too heavily upon the Earth with its construction or intentions. It was a quaint little village butted up against the glimmering cyan waters of the Caribbean Sea, near the southeastern tip of the island of Cuba. It was a town that enjoyed the simple things of early 20th century life in the tropics: vibrantly flavored fruits, loggerhead sea turtles waddling hurriedly over the moonlit sand, and the familiar and lovable squawking of snow-white seagulls flapping in the salty breeze. They were far from the port city of Havana—a place recently invaded by wealthy and overly-indulgent American tourists, high-rollers, and gamblers—and thus, had managed to survive and maintain a little bit of that past Cuban Paradise of old through the tumultuous, industrially romantic Roaring 20s.

But during the year of 1932, when the calendar flipped forward to the tropically inauspicious month of November, Santa Cruz del Sur was not under threat of any Bartender Invasion—contrarily, it was their very existence that was suddenly ticking down on the hands of the Caribbean’s clock. The people of this tranquil little seaside town could not know what was creeping up on them; could not conceive of the monster lurking just beyond the glittering horizon; a monster borne from that same turquoise water that was so warm, so lovely, and so inviting. And they wouldn’t know, not until they were caught in the thick glue of the tropical trap, of which there was no way to flee.

This is the horrific, heart-pounding story of one of the most extreme tempests ever conceived by the Caribbean’s fertile waves; the story of a Hurricane so Earth-shatteringly powerful, so hellishly unhinged, even the seafloor itself quaked in its coral-trodden boots. It’s the story of an unsuspecting city that found themselves caught in the furious rampage of a storm without limits… a city, that would be wiped off the very face of this Earth.

Situated at the trifinium of the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and Atlantic Ocean, the long, spiny island of Cuba was and is no stranger to tropical cyclone impacts. All 700+ miles of its length sits in the prospective paths of both recurving Caribbean Hurricanes, as well as meandering Cape Verde beasts that are pushed too far to the west by Atlantic ridging. Disgruntled by its unfortunate positioning, Cuba decided to arch its tectonic back in retaliation, creating a bony, mountainous spine that stretches ruggedly down the lanky island’s center, thereby making clear to any hungry, predatorial Hurricanes that the price of any landfall would be steep. And sure enough, time and time again, overconfident tropical cyclones found out the hard way that their destructive excursions through the country caused at least equal destruction to their own cores—the grave consequences of daring to trek across those painful, needle-like mountains.

But among the cyclones who accepted the reality, who could not or would not delay her sadistic gratification for changing entire coastlines, the 1924 “Cuba” Hurricane was among the most notorious.

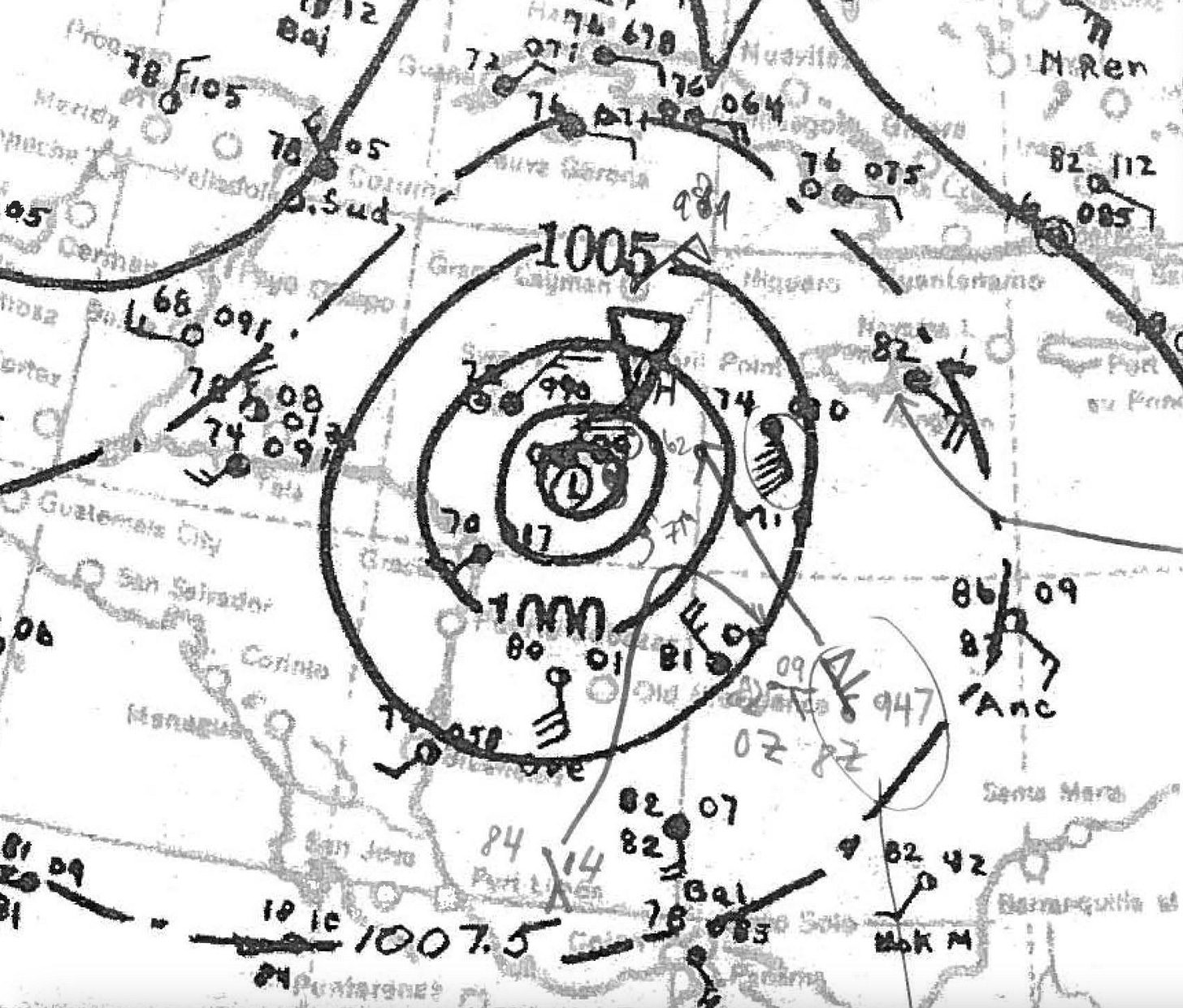

Forming on October 14 just off the coast of Honduras, the ‘24 Hurricane would turn out to be one of the most significant storms in Atlantic history, though it wouldn’t be fully realized until many decades later. The system tracked very, very slowly to the northwest during her newborn stages of life, gradually corralling in her large, broadened circulation into a tighter knit of convection about her center of vortical spin. By October 16, ‘24 had attained Hurricane intensity, and had only continued to slow her northward forward motion even further. She had decided that she was feasting on a particular delicious current of deep, western Caribbean warmth, therefore opting to begin an extremely slow and eccentric counterclockwise loop a few hundred miles off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula.

Two days later, without hardly moving an inch, ‘24 had reached Category 3 intensity—a Major Hurricane. Her sheer greed and cocksureness, fed by the seemingly unlimited supply of moist energy provided by the Caribbean (most storms moving that slowly would’ve weakened rather than intensified, due to a phenomenon known as upwelling, where a tropical cyclone churns up deeper, cooler waters by moving forward too slowly, thereby suffocating its own supply of conducive water temperatures), would be a sign of things to come.

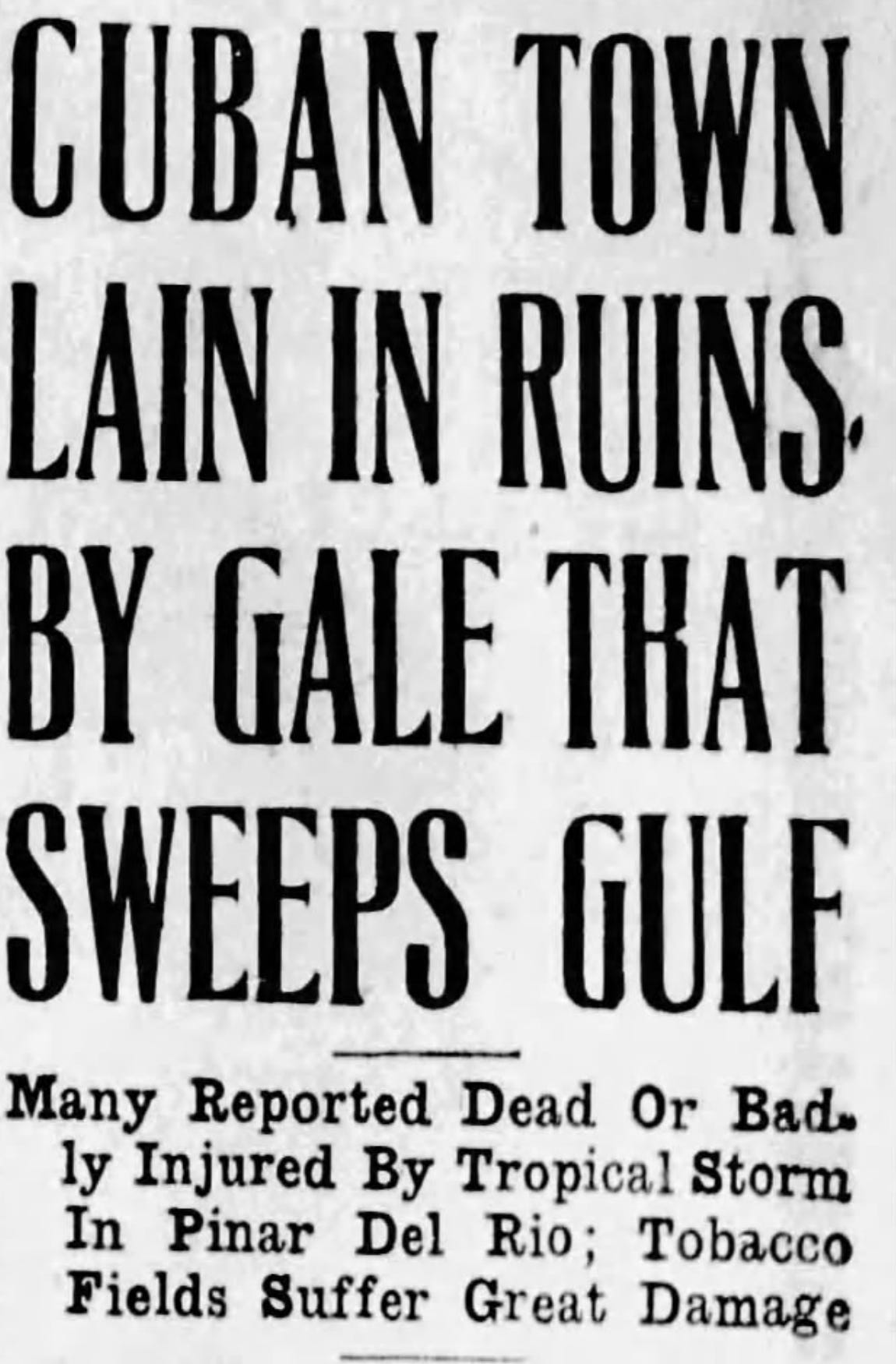

As ‘24 continued to strengthen, she lost all sense of whatever self-control she’d had left. Beginning to slightly accelerate to the northeast after completing her very lazy counterclockwise loop, ‘24’s core released the stimulant for rapid intensification. The Hurricane deepened passionately, growing fat and carelessly powerful from the Caribbean’s overabundance of tropical energy, and set her sights on Cuba’s Pinar del Rio Province. She crushed into the extreme western tip of the island in the dark of October 19th’s late evening, at an incredibly indulgent peak intensity of 910 millibars, and very powerful sustained winds of 165 mph. The landfall was devastating, severely damaging many towns (some of which suffered near 90% total infrastructure loss), leveling tobacco crops, severing all communications, and killing at least 90 people.

While it would take until a reanalysis of the tropical database in 2009 to verify it, the 1924 Cuba Hurricane is now recognized as the very first officially confirmed Category 5 Hurricane ever observed in the Atlantic Basin. A ship that was caught within the storm on October 18th of that year was the main data point of verification for this, as the crew onboard recorded a barometric pressure reading of 922 millibars (in reality, it was thought to be closer to ~917 millibars) from within the eye of the storm, the lowest recorded pressure ever measured in an Atlantic Hurricane at that time. Additionally, the peak observed landfall intensity of 932 millibars remains, to this day, the lowest atmospheric pressure officially measured over land in Cuba.

Feeling sufficiently satisfied from her terrible exploits in Cuba, ‘24 sought no further validation through terrorizing anymore coastal communities, and contentedly ended her life as an atrophying Category 1 with a landfall over Marco Island in southwest Florida. This second landfall caused very minimal damage and inflicted no casualties, thanks to fervid advanced warning from the U.S. Weather Bureau (a rare win for them in those primitive days of Hurricane forecasting).

But the belligerent exploits of the ‘24 Hurricane—in addition to another deadly Category 4 buzzsaw that cut through Havana itself just two years later in 1926—would soon pale in comparison to the mighty, unbelievable vortex of wind and water that would rise up from the Caribbean’s depths just eight years later. It would be a storm that looked upon her peers with contempt, in scoffing disrespect of what they’d accomplished, because she believed with a fiery confidence, that she could both do far better… and do far worse.

10 Days to Landfall—Just Like Any Other Season.

1932 was a bustling year for the nation of Cuba. Away from the rough and tumble countrysides, the island seemed like a beautiful sanctuary—mildly weathered, and heavily enticing to the outside tourist looking to get away from the cold, filthy drawl of New York City life and plunge their tired toes into the sun glazed waters of the Caribbean Sea. The tourist destinations were eloquent; the rum, cigars, and raw sugarcane, exquisite. At the center of this influx of kingpins and self-declared aristocrats, Havana stood proudly, a City caught in the explosive flurry of colorful Art Deco architecture that blossomed across the island during the 1930s. The sidewalks were crowded with swarms of well-coutured men wearing white straw boater hats, while baby blue Ford Model Bs rumbled down the streets with leisurely speed. Casinos and bars couldn’t be erected fast enough. Night clubs spread across the city like wildfire, hosting exotic shows and dancing performances for their affluent clientele. The tourism magazine Cabaret Quarterly looked back upon the city as, “a mistress of pleasure, the lush and opulent goddess of delights”. As an ode to the French influence of its exquisitely colorful buildings, its nickname was the ‘Paris of the Caribbean’.

But while Havana enjoyed the dance and drink of a patrician’s night life, the small towns and rural countryside of Cuba seemed to be living on an entirely different island. Living’s were made primarily from cutting sugarcane, the nation’s most valuable resource and centerpiece of economic exports; and exposure to the sincere, raw elements of tropical Nature was extensive. Homes and residences were not coral pink and ivory white chips off the Art Nouveau block, but usually more simple concrete dwellings and scrabbled wood lodgings.

Santa Cruz del Sur was one of these small towns; it had, within its municipality, no country clubs, only pure country.

The town lies ~327 miles to Havana’s southeast, in the country’s geographically largest Province, Camagüey (ka-muh-gway). In stark contrast to the vast majority of the island’s topography, the area is relatively low-lying, which allowed for local industries of cattle and flat-land farming to flourish alongside the sugarcane crops. The Province’s southern coast—Santa Cruz del Sur’s stomping grounds—is characterized by delightful sandy beaches, dense clusters of tiny island keys, and a bountiful, diverse coastal marine biome.

At that point in time, the area had no noteworthy recent history involving tropical cyclone activity—in fact, the only three Hurricanes that had been officially recorded as making landfall in the country of Cuba as a whole—the ‘24 storm and two “Havana” Hurricanes (1846 and 1926)—all carried out their destruction exclusively on the west side of the island. Thus, nearly a century’s worth of Camagüey’s residents had no comprehension of what it was like to pierce through the eyewall of a powerful Major Hurricane, to catch one’s breath in that eerily serene calmness of the eye after experiencing hours of heinously violent conditions, only to go through it all again on the storm’s opposite side.

There may have been a brief period of raised awareness following the damaging landfalls of the 1924 and ‘26 storms for Cuba’s population… but for the people on the eastern half of the island, those Hurricanes had been nothing more than a story they’d read in the newspaper, while others still may not have even known about them at all. And with November strolling around the corner for the 1932 season, both the Cuban people and the national weather authorities of the nation decided to let their guard down. Meteorologically, it was understood that the Atlantic should have been taking its foot off the gas pedal by that month, likely only to produce weak, sheared tropical storms or minimal Hurricanes in the Eastern Caribbean for the remainder of the year.

So, it was October 30th, 1932—and perhaps, on this day, one of Santa Cruz del Sur’s residents walked down to a pleasant stretch of Camagüey’s beaches. She knows only faintly the danger that Hurricanes can pose to the island—from second-hand stories, or distant rumors, or a brief glance long ago at a newspaper clipping. The testimonies of those stories—of great gales, flooding waters, and heavy tragedy—were just enough for the back of her mind to banter the possibility of one of those alluded great storms striking her own backyard during the late summertime months. But on this day, with November just around the corner, she holds her arms out in the salty breeze, calmly feeling that the time to fear, even in the slightest, for beastly and troublesome Hurricanes to suddenly come rolling over the horizon, was coming to an end.

So close… yet so far.

It was over ~1,300 miles away from that unwary little town of Santa Cruz del Sur, when a ship innocently cruising the open Atlantic happened to come across a loose collection of turbulent thunderstorms east of the Lesser Antilles. This group of thunderstorms were in the form of a late-season MDR wave—clusters of rain showers that emanate off the coast of West Africa and move generally westward across the span of the central Atlantic Ocean—though observations from the ship could not confirm much about the system’s anatomy, or its current organizational state.

The following day—Halloween, 1932—the wave had reached the island of St. Lucia, where local weather stations briefly recorded a dip in atmospheric pressure down to 1,008 millibars. While slight, this verified that the wave was indeed attempting tropical cyclogenesis. The youthful seedling of a storm crossed the threshold of the Caribbean’s doorstep later that night, eager and hungry for the candy of hot seawater that lay ahead. She would attain tropical storm force winds punctually afterwards, becoming the 14th confirmed storm of the ‘32 season… before disappearing into the satellite-free seclusion and haze of night as she moved steadily west.

There, momentarily free from the prying eyes of meteorology stations and the probing fingers of schooners and steamboats, the tempest’s winds shivered with temptation. She—Fourteen—was feeling the invigoration of the powerful, steamy jets of uplift feeding her cyclonic arteries, while her blossoming convective skin glowed like bubbling soap suds in the icy bath of the crescent Moon’s faint sliver of silvery light. The pure cane sugar candy of the Caribbean water was good, euphoric, and addictive… Fourteen sank her teeth into the dense layers of sweet, atmospheric moisture, salivating with sinister prescience as her convection gradually migrated towards the center of circulation, where it conjoined to cover the exposed core with an insulating mushroom of thunderstorms. For the first time in her life, her frigid cloud tops were genuinely beginning to swirl, and it would be at this point that a messy, primordial eye would start to blink open blearily.

On the abnormally breezy morning of November the 2nd, the residents of the Dutch territories, known today as the ABC Islands, awoke to gray curtains of heavy rain showers rolling off the northern oceanfronts. At first, people simply listened as the glistening downpour pattered the boards of their palm planked roofs, thinking nothing of the oceanic storm—these were the tropics, after all, and rainfall was a near-daily occurrence. But as the afternoon progressed, the ocean began to writhe itself into a chopped up tumultuous soup of sea foam and white sand, sending waves cascading up the beaches of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao with aggression. Suddenly, it became apparent that this was no everyday, run of the mill Caribbean thundershower. This was something more… but could it be? This far south? This late in the year?

Indeed, Hurricane Fourteen had reappeared less than a hundred miles northeast of the ABC Islands, a trio of cayes that sat less than 60 miles north of Venezuela, at most. It is rare, and highly unusual, for Hurricanes to stray this far to the south, where the equator begins to strain the efficiency of the Coriolis Effect on convective vorticity. But Fourteen was unwavering in her path and mission, continuing to steadily organize despite her low riding latitude. That day, the winds embedded around her center surpassed the ~74 mph mark, granting her the honor of Category 1 Hurricane status.

The storm lashed the Dutch islands and the northern coast of South America for over two full days, slinging bands of rain over the beaches and through the rainforests. On Curaçao, the massive, raucous, and relentless surf pounded the island’s maritime infrastructure, destroying docks, hindering harbor traffic, and severely damaging Dutch naval defenses. As the enormous Hurricane crept closer, the density and hardness of rainfall increased; in Columbia, a location not exactly known for its propensity of tropical cyclones, conditions worsened rapidly as whipping curtains of milky white precipitation roughly lashed the rainforest canopy. On November 3rd, Fourteen, whilst simultaneously roaring with life as her winds climbed further over ~100 mph (a Category 2 strength), closed in a mere ~50 miles to the north of the Cape of Punta Gallinas, Columbia—a place that is no town nor city, but simply a lighthouse that delegates South America’s extreme, northernmost point.

Fourteen’s developing eyewall never actually reached the Columbian coast, yet she still unleashed a damaging plethora of conditions throughout the country’s north—attestation to her already massive size. Fourteen’s rain seeped deeply through the soily creases of Columbia’s undulating slopes, lubricating the subsoil and inducing mudslides that razed tracts of forest and swallowed swaths of unluckily located railroad lines. Vivacious winds tore down miles of telephone lines and ripped open poorly constructed roofs. Tawny torrents of water roared down valleys and flooded dozens of rural towns; agricultural communities suffered the worst damage, as acre upon acres of precious banana crops were flooded, uprooted, and ultimately ruined. Other townships near the coast faced severe damage from both the wind and the floodwaters—in particular, the village of Sevilla was reportedly completely destroyed by mudslides and flash flooding.

Conditions slowly started to normalize by November 4th, finally indicating an end was near to Fourteen’s skirting passage of South America as the system halted its bizarre southwesterly movement, and leveled off to a due west motion while accelerating very slightly. Through her gentle movement and large radius, the storm had caused significant damage over a wide swath of South American coastline…

But her feelings were nowhere close to satisfied.

5 Days to Landfall—The Storm To End All Storms.

The Caribbean Sea in 1932 was a treasure chest of energy—a tropical Pandora’s Box, waiting patiently to be opened and unleashed by the wanderings of an ambitious tropical cyclone.

Late on the night of November 4th, with the half-Moon ascending the charcoaled sky, and as the pure heat energy of oceanic steam wafted off the chaotic Caribbean surface, the Hurricane’s winds grabbed the moisture and brought it to the central queen of the storm’s center. Once delivered to the cells of the eyewall, Fourteen then inhaled the euphoric vapors through the updraft of blooming thunderstorms, instilling within the storm a new-found rage that felt so wonderful, and satisfying, to release.

Placing ourselves in the moment, we watch as she exhales the air via the bitterly cold cloud tops of those thunderstorms, now likely reaching temperatures under -100 ℉. She feeds the spent air back to her spiraling outflow patterns wrapped around the finger of her periphery, where it will sink back to the lower troposphere to be recharged and re-consumed. She had encountered her proverbial Battle of the Alamo, but as victoriously seen by Mexico.

In response to the vacuum created by Fourteen’s winds, as they pull the air from the surface and up through the eyewall, the air within the clearing eye rushes downwards to fill in the atmospheric gaps, frantic to try and maintain Nature’s insistence on entropic balance. Freed of Davy Crocket resistance, the air pressure in the eye plummets; and the winds, daring the core to keep up with them, spin faster and faster.

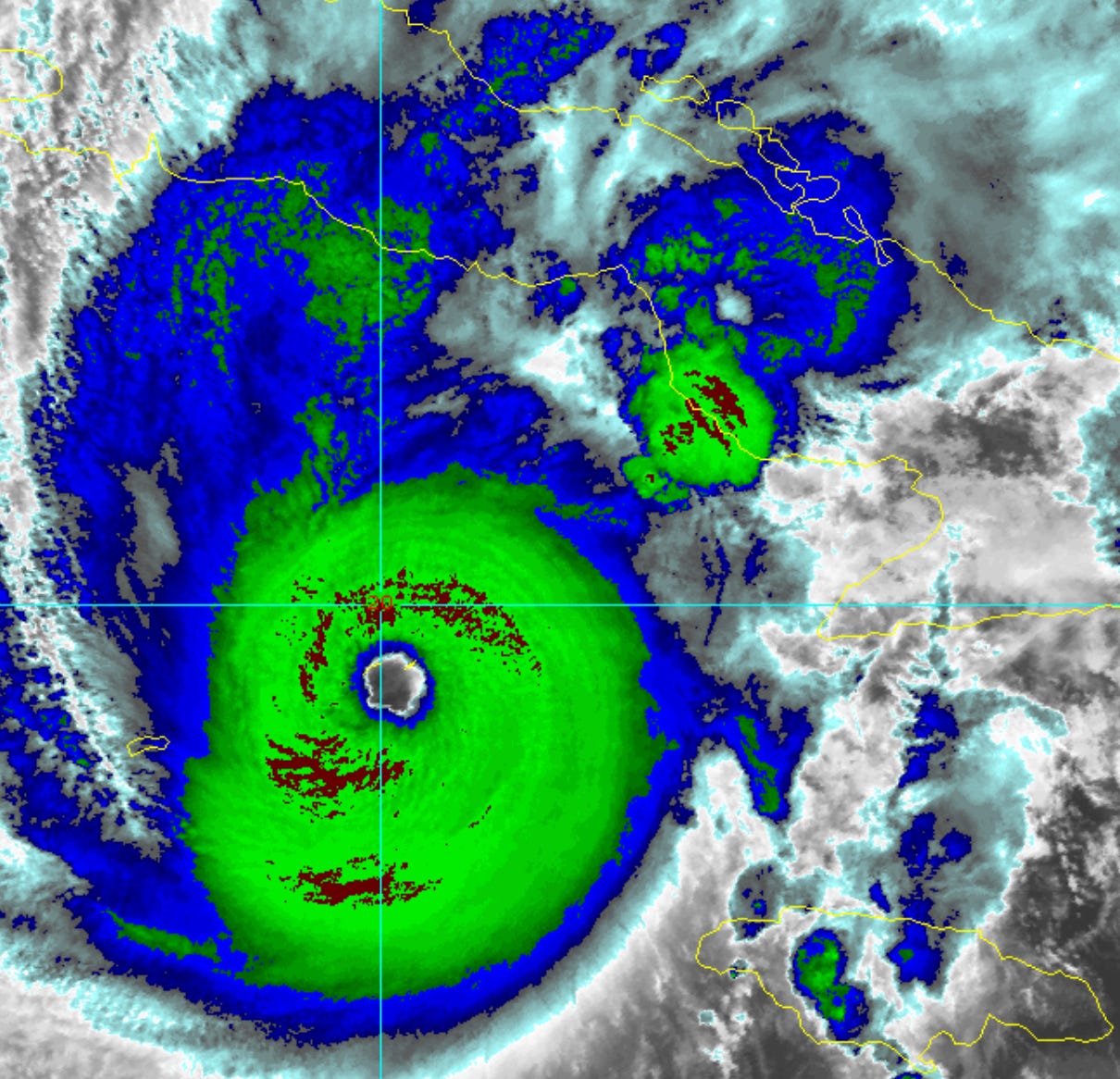

Fourteen became a Major Hurricane that night, likely spinning up with sustained winds between 115-120 mph. She’d very carefully planned her internal dynamics during her first five days of life: organizing the supply lanes for moist air, stacking the weapons of her convective layers that she would need, and choosing, precisely, the exact best time when to move, and where. With the appropriate time taken to get her core twirling efficiently, the sheer inertia of Fourteen’s thunderstorms would not interfere with the coveted rapid intensification phase that she so desired.

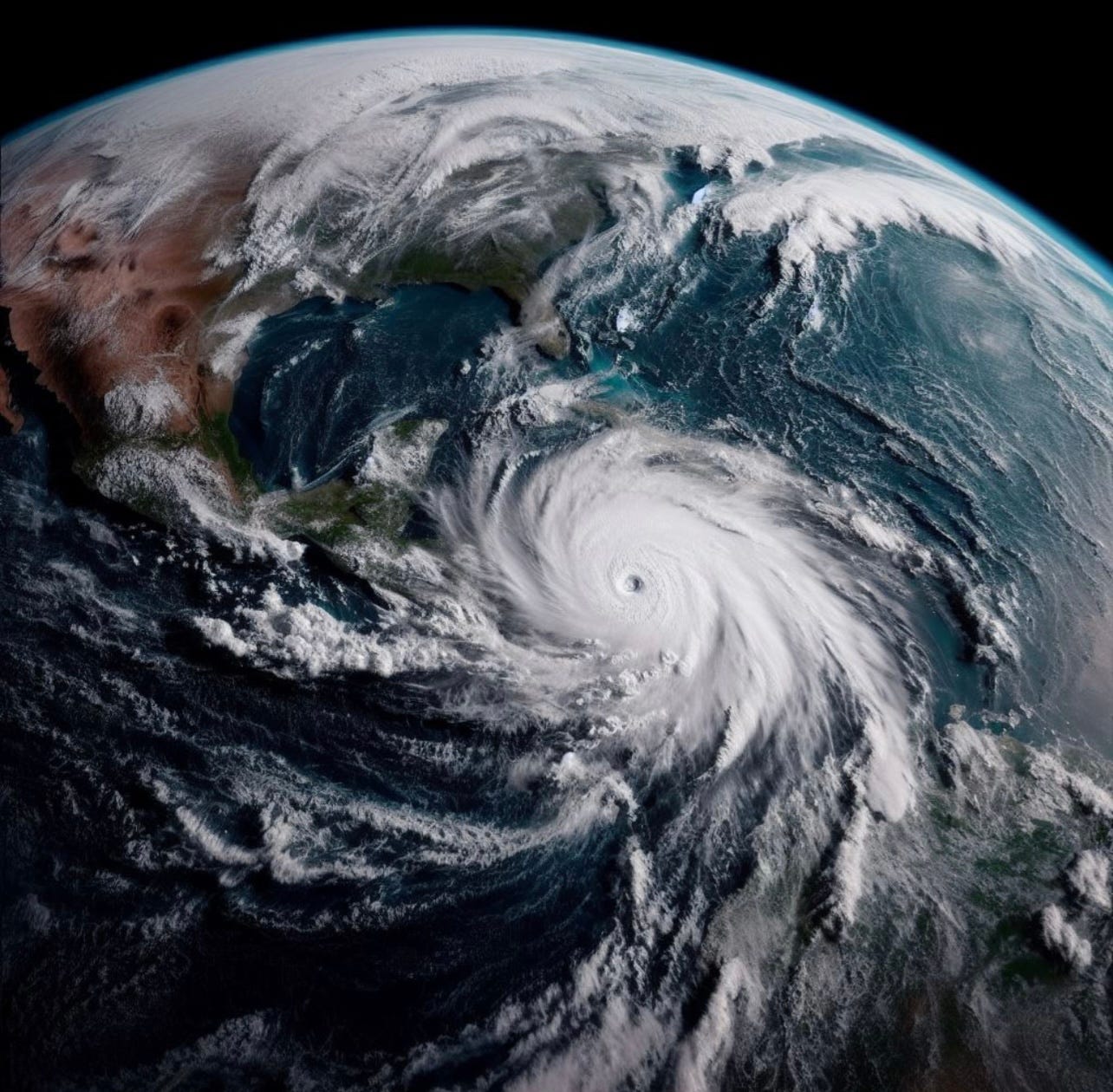

The plan was perfect—from chalkboard birth to flawless execution. The final pieces of the puzzle fell into place, assembling a primary eyewall of such incredible perfection, that none other comparable have been observed in the Atlantic to this very day, 91 years later. An immense CDO of supple, billowing convection exploded in an impassioned, flaming rage around the eye, growing an impenetrable marshmallow of homogenized, concentric rainbands to safeguard the core from the outside world. The eye itself, meanwhile, was drying and warming faster than an afternoon in the Sonoran desert, plunging its central pressure well below ~930 millibars. Outflow banding arched out to great lengths from the Hurricane’s center, possibly stretching hundreds of miles across. By the evening of November 5th, roughly ~24 hours after first reaching Major Hurricane strength, the Hurricane’s furious winds eclipsed ~157 mph, making her a monstrous, Category 5 beast of all beasts. Her forward movement once again slowed precipitously, screeching to a west-northwest crawl, as she wanted to greedily scrape up and pull in as much of the juicy, compelling fuel sitting beneath her as she could. The western Caribbean had been virtually untouched from the previous storms of the 1932 season—and Fourteen intended on violating every inch of it.

All of this, in the month of November—hardly known for Hurricanes and tropical gales, it was the time of year intended for orange leaves, breezes that bit the lungs, and bountiful feasts of autumn-spiced food. Yet, shielded in the depths of the Caribbean, the storm who simply called herself Fourteen was tearing at the air and the waves with a less-than-stoic temperament.

The entirety of the sea now trembled under the terrifying power of the very storm it created. Pandora’s Box was open, and now, there was no turning back. There was no escape.

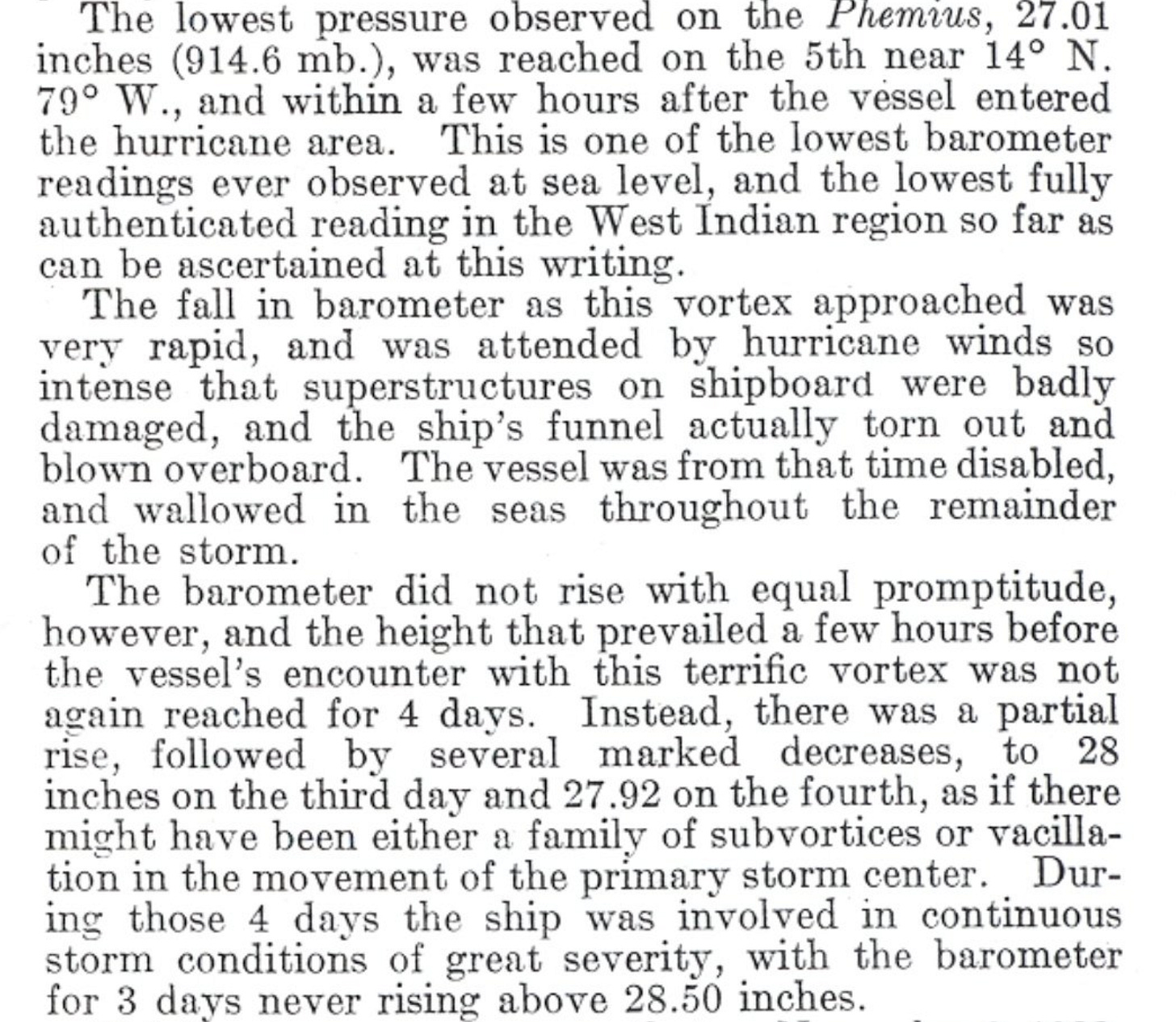

Earlier in the day of November 5th, outside the Category 5 Hurricane’s grasp, a British steamboat passenger ship, the S.S. Phemius, could sense the nearby whirl of a powerful, ocean-going vortex. Subsequently, the vessel received several weather bulletins regarding the storm, and heeded the recommended routes of travel as advised with the forecast path of the storm—but soon, they would discover the terrible consequence of this decision, as said weather forecasts were based too heavily upon historical tracks of November Hurricanes. Because of the lack of well-documented late season tropical storms (particularly those of intense pressure gradients), the forecasts given to the S.S. Phemius were fundamentally flawed.

It wasn’t long before the Phemius’ Captain, crew, and passengers realized what terrifying fate they had found themselves floating towards. The sky began to darken forebodingly, casting deep shadows into the Caribbean’s waters that transformed the depths from sparkling curtains of beauty to an impenetrable teal abyss. Thunder rumbled from the strobing flash of lightning overhead. The wind strengthened to the point at which sea spray billowed off the crests of the increasingly large waves, adding a taste of salt to the rain that slowly began to flow more horizontal than vertical. Trepidation spread like a virus between the closely packed voyagers and crew.

The next three days for the S.S. Phemius and her travelers could only be described as an unparalleled tropical hell on Earth. In the blink of an eye, the ship was hopelessly trapped inside the inescapable and merciless bowels of a Category 5 Hurricane, whose inner banding structures within the CDO took turns at brutally tossing around the forlorn vessel. Captain Evans sent as many SOS signals as he could, but they had already passed the point of no return. They were too far within the storm, and nobody could help them—nobody could save them from what would come next.

Picture what it would’ve been like in the interior of Fourteen early on November the 6th: as the gray dawn rises, Phemius only continues to be sucked in closer and closer to Fourteen’s intense nucleus. The hull of the ship creaks and cracks with the pounding of waves that arch dozens of feet high; Phemius is thrown upwards, then plunged bow-first into the ocean surface, over and over and over again, each time sending a white explosion of saltwater lunging over the deck. The feet of the crew-hands are swept out from under them by the rushing seawater, and they fall to the deck roughly. A plethora of ropes and wires shudder loudly, dangerously, whipping and threatening to snap in half. The masts bend and bob, and in a climactic moment of terror and chaos, the primary smokestack is ripped clean off of Phemius’ face, and thrown haphazardly into the sea. Beneath the deck, it may have been that water was jetting wildly through pried cracks in the hull. Crewmen rush desperately to somehow stop the bleeding, wading through growing pools of water in the claustrophobic corridors. Everyone grips tightly to whatever they can, holding frantically to avoid being either thrown off the deck or smashed between the walls in their cabins and rooms. The damage was extensive; soon, Phemius became completely immobilized, and was now a powerless, folded paper boat tediously bouncing between the massive waves. Stuck, paralyzed, and battered, they were at the complete mercy of the storm to end all storms.

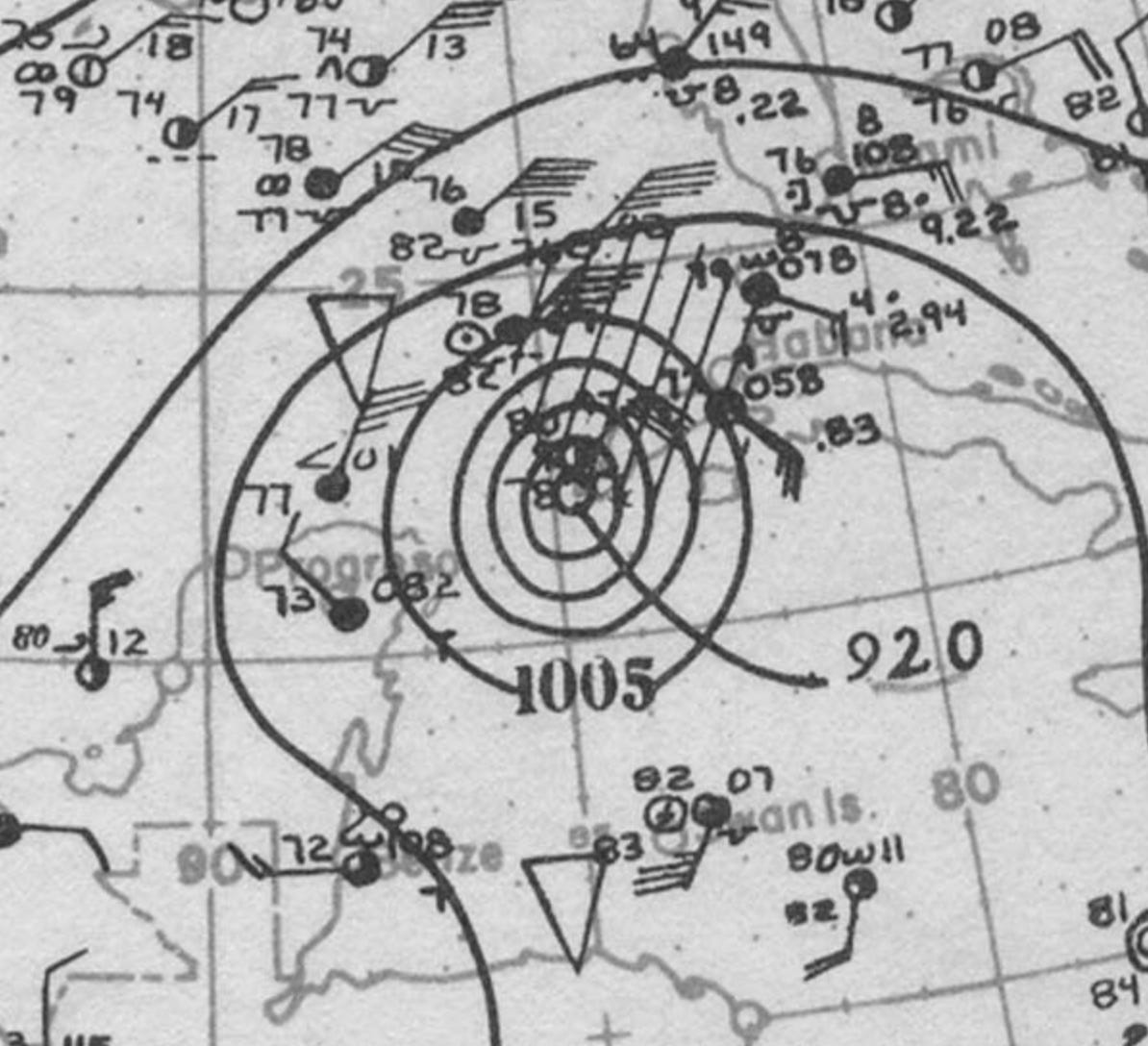

Phemius would never make it in the eye of the Hurricane that hellish morning of the 6th, but they were entrenched thickly in the pure, unimaginable violence of Fourteen’s extremely robust eyewall. And it was there, between the gnashing teeth of winds that the Phemius’ crew estimated to have been as high as ~200 mph (translating roughly to ~175 mph sustained), that one of the most profound and historic raw, in-real-time barometric air pressure readings was ever recorded. At the height of the storm, the inches of mercury onboard the Phemius fell down to an ear-shattering 914.5 millibars—and it was the fact that this observation occurred inside Fourteen’s eyewall, and not within her eye, that meant her true pressure was much, much lower.

In other words, 1932’s Hurricane Fourteen very likely had a minimum central pressure well below 900 millibars at her peak fit of fury during the morning hours of November 6th, which unofficially makes her among the top four most powerful Atlantic Hurricanes in recorded history. On top of this, her quintessentially flawless eyewall maintained Category 5 sustained winds for an unprecedented 78 consecutive hours, the all time record for an Atlantic Hurricane that stands to this day.

It’s hard to comprehend the body-rocking fear that surely wracked the crew of the Phemius over the course of that day, particularly during those pre-dawn hours of cyclonic horror, when the sky was bruised bluish-black by the screaming winds of the storm’s wicked, relentless eyewall that was impeccably perfect and stable. More than a fleeting thought it was for them that their deaths seemed all but imminent—survival inside a Hurricane such as Fourteen felt like it should’ve been impossible. But miraculously, the crew and passengers realized that, even though the fearsome winds still thrashed in a whiteout wall of pelting rain well into the afternoon, that they were losing their vigor gradually—whether it was from Fourteen slightly weakening off her peak, or the ship simply meandering out of the eyewall, cannot be determined. In a very cautious exhale, Phemius’ travelers dared to wonder if, somehow, against all odds, they were going to make it through after all. Still, they endured Fourteen’s extremely stormy conditions, and continued to watch in horrific awe of their barometer that refused to rise.

Finally, their prayers came to an ultimate conclusion on November 8th, when a salvage tug happened to come across the bruised and battered ship, floating on its final limb. As it turned out, Captain Evans’ SOS messages had been received earlier, and several search missions, including the deployments of two U.S. navy vessels—the USS Overton destroyer, and the USS Swan minesweeper—had set sail into the storm’s periphery in search of the Phemius (both U.S. Navy missions would have to be called off due to the raucous conditions and poor visibility brought on by Fourteen’s massive radius of dangerous storminess). It wasn’t until the Hurricane finally tossed the Phemius from its eyewall that the tug was able to locate and tow the tortured ship to safety at a Cuban port. In the months that followed, Captain Evans was awarded for his actions that preserved the lives of his crew amidst the dangerous conditions inside the vicious cyclone, while simultaneously being slapped on the wrist by the Phemius’ owners for steering the ship into the Hurricane in the first place.

To this day, the harrowing journey of the S.S. Phemius remains one of the most remarkable observations of a Category 5 Hurricane ever endured. The raw data the ship returned displayed a sheer complexity inside the storm’s CDO that had previously never been conceived, as well as being the sole source for the data that would be used to officially affirm Fourteen’s peak intensity: >175 mph maximum sustained winds, with a minimum barometric pressure of <915 millibars.

But the story does not end here… because this great Hurricane of near-unprecedented size, power, and intensity was making a curve to the northeast, in heated, craving pursuit of her ultimate prey:

Camagüey Province, Cuba.

24 Hours to Landfall—Why Isn’t Anybody Worried?

Fourteen had executed one of the most precise and exemplary exploitations of surrounding conditions that were near-perfect for cyclonic intensification. Not only did her massive eyewall attain close to record-breaking intensity, but she also held that intensity for longer than we’ve ever seen in the Atlantic Basin. The primary eyewall’s stability under the pressure of such volatile and precariously strong winds is almost incomprehensible; only Hurricanes Allen (1980) and Irma (2017) could be remotely comparable, in terms of achieving a Super Typhoon-like duration at the feared maximum intensity on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale for so long.

During the great storm’s leisurely curve at her historic, seething strength, the Caribbean’s shipping routes were in absolute chaos. Outside of the Phemius’ treacherous exploits, several other freighters and steamboats—most notably the San Simeon and Tacira vessels—were heavily damaged upon getting on Fourteen’s bad side, which she seemed to dispose to anything and everything in her path. Many were disabled, just as the Phemius was, and required tows to shore.

But the scene was much different in Santa Cruz del Sur, Cuba. Here, there would be very little talk among the local residents of any sort of Hurricane in the Caribbean until late on November 8th, when the storm was coming up just ~24 hours to the southwest. The National Observatory of Cuba had known of the storm’s existence and had been tediously preparing for a potential Hurricane landfall as early as November 5th, catching wind of the reports of ships like the Phemius who had encountered the Category 5 behemoth out at sea. However, just as with the forecasts given to the Phemius misled Captain Evans’ to steer his ship into the storm, the National Observatory was lacking in its own, definitive confidence, as they could not reconcile the fact that Fourteen was not following the climatological track of what typical November cyclones should. Thus, they remained strangely silent as the Hurricane progressed, putting up no Hurricane warnings and sending no public bulletins to interests in southeastern Cuba.

While confusion and indecision plagued Cuba’s national meteorologists, Jamaica was getting a small taste of Fourteen’s incoming madness. While the island never experienced sustained winds over a relatively modest ~70 mph, strong gusts still managed to wreck almost half of the banana crops that were integral to the nation’s economy, toppling over 2 million trees and inflicting $4 million in total damages. Additionally, an American schooner, the Abundance, was beached on the shore of Morant Point. For Fourteen, this was merely child’s play, like sweeping up minnows in a net on the side while simultaneously deep sea-fishing for marlin—but as she rolled by Jamaica, word began to trickle out. As the journalist Rafael Valdés Jiménez recalled:

"I am an English translator and for years I dedicated myself to monitoring foreign stations. At eight o'clock at night on the 8th I heard the calls of a North American reconnaissance plane, a kind of "hurricane hunter", then called "storm riders." They called the Western Bureau of Meteorology in Florida reporting that they were approaching the storm that was in front of Punta Negrín in Jamaica. They reported winds with a speed of 250 km per hour, and that it was heading towards the north. This was at 12:15 at night more or less. I took a map and saw that Santa Cruz del Sur was in that direction, so around one thirty in the morning I called on the phone and spoke with one of the telephone girls who were at their position and I told her more or less like this: Girl, tell the people to get out of there that the cyclone is going to Santa Cruz! And she told me: Valdés Jiménez, no one answers our phone anywhere. No one answers. Things are bad. and I have water here on the blackboard, on my knees. I told him well, then get out of there and look for a boat, but leave urgently. Get out right now!... and then the communication was cut off. The three girls drowned in their positions.”Shock perforated through communication operators and monitors in the region as it suddenly became apparent that an enormous, intense, 155 mph high-end Category 4 Hurricane had seemingly appeared out of nowhere. By now, Cuba’s National Observatory, also seeing the reports, could no longer deny the grim truth that a Cuban landfall was imminent. Santa Cruz del Sur’s residents, too, knew now that a storm was coming, and by 10:00 pm local time on November 8th, the first of the Hurricane’s rainbands were rolling in from the ocean, and the waves near the coast suddenly became a choppy tumult. Additionally, the local fishermen, with an instinctual scent for the waves, insisted vehemently that a very strong Hurricane was imminent.

Finally, around 2 am in the morning of November 9th, the National Observatory, still acting bizarrely hesitant given the rather extensive information they now had on Fourteen’s strength, position, and vector of movement, sent a message to receivers in Camagüey city, Camagüey Province’s largest municipality, situated 48 miles north of the Caribbean coast:

“Hurricane center seven p.m. 15O miles west of Jamaica moving north northeast. You must raise the signal for possible strong storm winds first thing in the morning. More danger for the Camagüey area, but it is possible that the trajectory leans further to the northeast and crosses the center over the East.”In response, the Camagüey receivers passed the message on to Santa Cruz del Sur, using emphatic additional language in hopes of rousing attention to the terrible danger that they feared was coming the town’s way. But this did not initially happen, as the language of the National Observatory’s message—the key sentence, noting the possibility that the storm leans east of Camagüey Province entirely—instilled a false sense of security in Santa Cruz del Sur’s authorities, despite stormy conditions having already reached the town. This meant that the only warning that Santa Cruz del Sur finally received, which came at an unbelievable and perplexing short notice of less than 12 hours before landfall, wasn't even immediately taken that serious by the town’s officials. There were no real attempts for evacuation, meaningful preparation, or warning; the lack of concern was so extreme, it was almost cocksure. The residents of the town themselves remained almost totally oblivious to the Hurricane itself, believing the bands of thunderstorms to be nothing more than any other overnight tropical shower.

Meanwhile, for Fourteen, her long sought goal was now within her perilous grasp—Camagüey’s destructive demise. A painfully exquisite plan the great Hurricane had conceived of long ago, back when she was nothing more than a meager tropical storm a thousand miles away from Cuba in the Lesser Antilles. And now, she was just hours away from fulfilling that ultimate climax—but first, she wanted to feel a prelude to the disaster she pined to crush Camagüey Province with.

The Cayman Islands were next in line for Fourteen’s tropical woodchipper. From the late hours of November 8th heading into the 9th, the Hurricane’s eyewall, having weakened down from her burning Cat 5 peak but still packing catastrophic sustained winds of 155 mph, plowed through the island chain unflinchingly, causing absolute and unprecedented devastation with a giddy, uncontrollable frenzied glee.

The scale, the power, the horror, was utterly unthinkable. As Fourteen’s eyewall came across the tiny island of Cayman Brac—a plot of sand just 12 miles long and an average 1.2 miles across—it completely disappeared under what was possibly the highest, most unimaginable storm surge ever recorded from the eyewall of an Atlantic Hurricane. A convulsing tsunami of seawater ~33 feet high destroyed, killed, or pulverized every structure and living being on the island.

In the midst of the apocalyptic inundation, 100% of all the island’s structures were practically swept out to sea. People who amazingly were able to swim through the heinously churning waters had to be lucky enough to find a tree over 30 feet tall… these people would be the only survivors, as all 69 others on Cayman Brac drowned in the catastrophe. A barometer reading on the island clocked the minimum pressure down to 939 millibars while in Fourteen’s eyewall, supporting a core pressure as low as the 910s.

While the other Keys of the Caymans suffered significant damage as well, Cayman Brac was the only one that experienced the Hurricane’s true eyewall, as the storm’s center was passing to the east, and Brac was the easternmost island of the territory chain. This is what resulted in the unfathomably large storm surge that ensued.

But it was not just Cayman Brac that was being decimated; dozens of ships docked in and around the island chain were battered, tossed, turned, crushed and capsized by the mighty caterwaul of Fourteen’s unstoppable eyewall. The Hurricane manipulated the Caribbean water at will, bending, pushing, and pulling at the source of her very creation and growth, without thanks or courtesy. Many ships sank completely, often in the shallow-watered harbors they’d believed would protect them. Another 40 lives were lost out at sea, giving Fourteen over 110 casualties under her belt… and she was just getting warmed up for her final, pernicious approach.

At the same time as the Caymans were being plunged into cyclonic hell in the black void of night, the residents of Santa Cruz del Sur, lying ~130 miles to the northeast of Cayman Brac, slept relatively soundly to the rain that poured outside their homes, and the breeze that tapped at their shutters. It may be hard for us now, living in the modern era of satellites and computer model forecasts, to comprehend how so many people could be so oblivious to such a massive and powerful storm rolling right up to their doorstep. But because there were no sophisticated methods for tropical cyclone tracking, and because the Cuban National Observatory failed to communicate the grave situation to the rural communities in the country’s southeast in a clear and sufficient manner, the citizens of Santa Cruz del Sur and southeastern Cuba had no idea that Hurricane Fourteen was coming.

As the first masses of bubbling storm clouds crept up above midnight’s dark horizon on November 9th, 1932, the Clock for Camagüey’s Shores ticked down to zero.

Fourteen, at long last, had arrived.

The Clock Strikes Landfall.

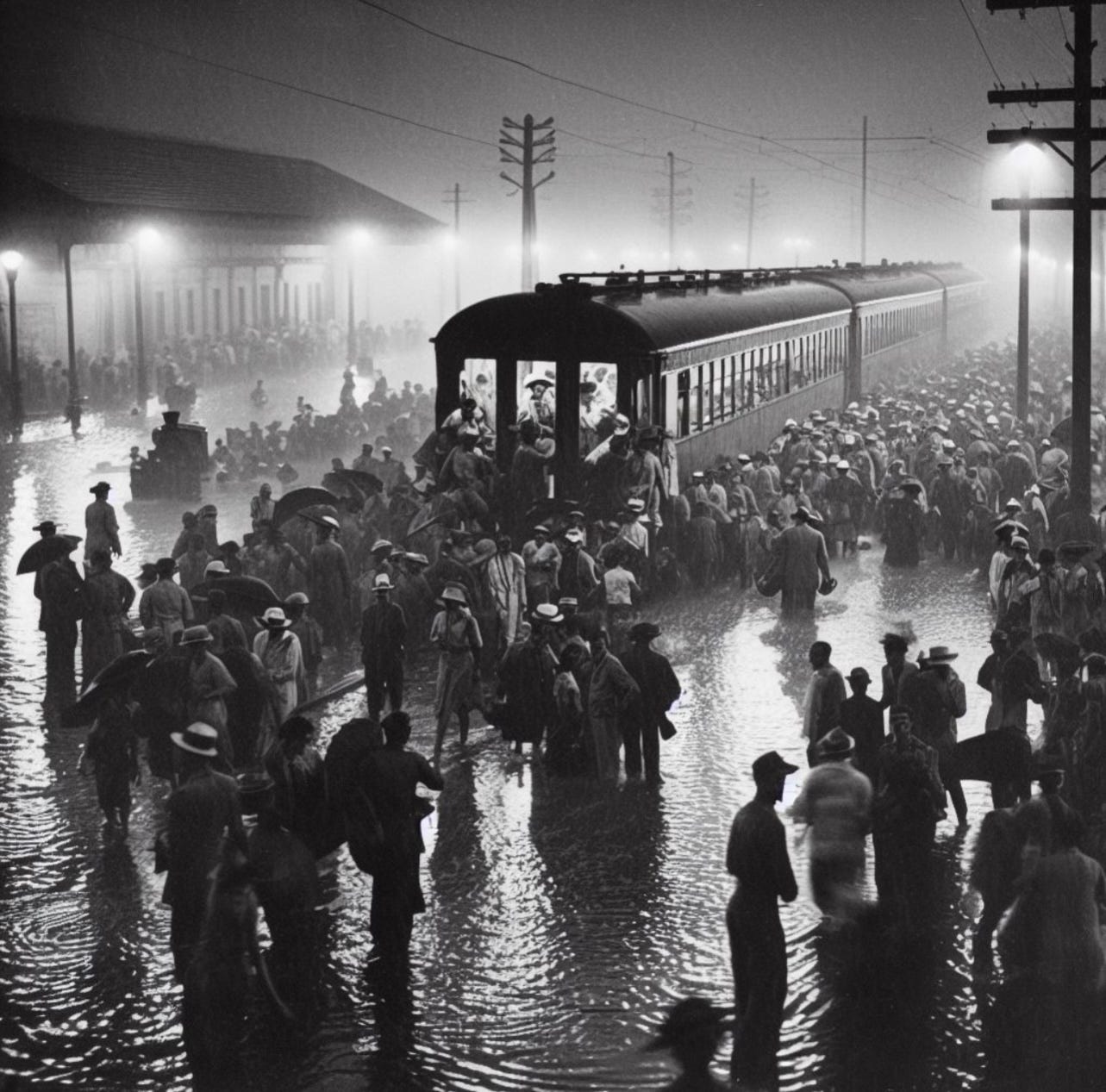

At 4 am local time, November 9th, 1932, the winds began to pick up in Santa Cruz del Sur. Seawater rushed up the beach with haste, overflowing the shallow dunes and pouring onto the seaside streets of the town, slowly inundating the ground with a shallow, wet shell that rippled in the reflection of the streetlamps. Just two hours previous, local authorities had expressed very little worry or urgency about the incoming storm. But now, as dire warnings flooded in from the ships stationed around the Cayman Islands, and a trickling of distress from residents who could see the rushing oncoming of the waves, Cuban officials realized, with a sickening pit in their stomach, that the dreaded, extremely intense Hurricane Fourteen would not be missing to the east of Santa Cruz del Sur, as they had previously hung their hats on. Now, in a panic that came too late, they scrambled to organize evacuations out of the tiny city via passenger trains—but by this time, there would be no hope of evacuating the majority of Santa Cruz del Sur’s residents. Authorities, both local (Camagüey) and national, were forced to concede the horrifying reality that only a select several hundred people could possibly be shipped to safety before Fourteen’s teeth sank deep into the city’s heart.

In the pitch dark of the pre-dawn night, the trains at the Santa Cruz del Sur train station were hastily commissioned for the evacuation of the town’s residents. The gargantuan scale of Fourteen’s wind field and CDO meant that intense sheets of tropical rainfall were already cascading down over the town, reflected as golden curtains flowing past streetlamps and illuminated windows, while a whirlwind of sustained tropical storm-force winds bristled cooly, pushing waves and water up the beaches to the south in a continuous manner.

Soon, congested crowds and huddled groups of people crammed the wooden platform of Santa Cruz del Sur’s Rail Station. Scared, cold, and confused, they pulled their children and/or loved ones beside them tightly, their hair and clothes soon thoroughly soaked to a sopping mess; all while train and town officials attempted to direct this chaotic flurry of confoundedness into a neat and orderly filing onto the open train cars.

With every hour that ticked by, the surreal tumult of down-pouring precipitation slowly transformed into a near-whiteout. Telephone and power lines above rattled and bounced as the winds increased; the station lights began to flicker. The rain descended harder, a relentless torrent of tears shed by the eyes of the Hurricane’s crying, convective storm clouds. Rain induced floodwaters started to rise with dismal rapidity around the ankles of the increasingly panicked crowd; isolated hysteria may have even prompted groups of people to begin pushing and shoving their way onboard—or, a lack of comprehension for what the incoming Hurricane was going to unleash could’ve leant an equally likely scenario of a less raucous riot at the train station during that fateful night. Whatever the case, there is no doubt of the absolute and icy terror that would’ve been rushing through these people’s veins as the storm spun overhead.

At first, some of the trains were able to ship off with their full loads of evacuees, bringing them to the relative safety of inland Cuba. But as the sunrise hours of the 9th arrived, with conditions creeping closer to the extreme, the floodwaters had risen to a dreadful, horrific point of no return.

For the remaining crowds of Santa Cruz del Sur’s residents at the station, shivering from both fear and wet frigidity, after being exposed to the interminable wind and rain for many dark hours, they were able to feel a small flame of hope ignite within themselves, when their turn to board finally came. Some made it into the train cars fully, likely exhaling an incredible sigh of relief just from finding refuge from the cold deluge outside. Other faces outside looked in through the bright windows hopefully, wading through the frightening dark waters, but feeling their ride to safety was just a few steps, just a few bodies ahead of them.

But the sense of relief would turn out to be excruciatingly short-lived, as the station officials, in a single, heart-dropping, gut-wrenching moment, tediously informed the prospective evacuees that the last trains could no longer depart out of the town. For the people onboard those very train cars, lumps surely swelled in their throats. We can intuitively surmise, that with numb legs, they shuffled back outside, stepping down and splashing back into the floodwaters and back into the fear, feeling their skin once again pelted by the thrashing rain.

With a dawn unlike Camagüey had ever known, Santa Cruz del Sur became an island in the depraved isolation of a cyclone’s moat of inexorable vorticity—cut off from help, from hope, from the entire outside world.

Now… there was no escape.

Using our intuition of history and science, we can envision that on the other side of the town, within audible proximity to the coast, a woman awakes from her bed by the tapping of palm fronds against her walls, the dim silver gleam of morning’s light dripping through the windows splattered with horizontal rain. Drawing up the shawls of her nightgown, she edges out onto her front porch, her toes curling when she steps into the cold pools of water that had collected on the boards of the front deck. The woman shields her face from the misty raindrops being blown sideways by persistent gusts of wind. There was a smell of salt on the cold, foul breeze that leant itself to be more than just a typical, stormy squall; and in the distance, the woman could hear the pounding roar of the waves crashing unto the beach. She promptly decides to close the front door with a squeak of rusty metal hinges tormented by years of salty air, as a nervous apprehension tingles through the veins of her fingers.

These would’ve been the scenes unwrapping all around Santa Cruz del Sur that terrible morning; from families to sugarcane cutters to fishermen, from the people who’d never known of the storm drawing near, to the ones who’d just returned reluctantly from the crowded train station in dread; dejected and afraid of coming home to what they feared to be one massive, tropical deathtrap…. they didn’t realize how right they were.

After hours of wearing wind and and rain, and with a penetrating sharpness of the Hurricane’s outrageous, piercing teeth, the massive Eastern eyewall of Fourteen tore straight into Camagüey Province, grueling a thick flow of onshore fury directly into Santa Cruz del Sur. With cruel, back-breaking winds of 150 mph, and a crippling minimum core pressure estimated at 918 millibars, the Hurricane plunged the victimized town into a watery underworld, screaming in fiendish excitement at finally meeting her White Whale. But unhampered by an Ahab peg-leg, her flaming intensity had no limitations to the fanatical fury she could unleash. It was the culmination of days and days of anticipation, a frustration she took out in her ruthless beating of the Caribbean water into submission. It was during those long days that Fourteen impatiently churned, collected, and accumulated millions upon millions of gallons of loyal seawater to help her in her maniacal mission. She knew full well that a landfall would bring her her own, savage demise; but the chance to chop and spear her storm surge into Camagüey’s writhing coastline was too much for her to resist.

Our minds can see that families must have pulled their children tighter in their arms as a shrieking that sounded just like the whistle of the last train that left the city—only now, multiplied by a thousand and laced with a screaming nefariousness—screeched outside in the native tongue of Major Hurricanes. People cowered in corners, away from windows, maybe even under mattresses, as the wall boards creaked, and the roofs moaned precariously. In the streets, many were caught outside when the eyewall suddenly arrived; the final things they saw was the effortless disintegration of the roofs of nearly every structure around them, creating a vortex of flying wood and debris. The people tried to run, tried to find cover as the savage power of gusts over 170 mph knocked them to the ground, but there was nowhere to flee. Pitilessly, the eyewall’s vicious gale cut down entire groups of flailing people, impaling, crushing, and killing them in droves, with a deafening vortex of knife-like splintered boards and broken glass. The slaughter did not step there, as even more still, who were seeking shelter inside their homes, found themselves impaled by the shreds of their open architecture tropical homes, while others were smashed by the total structural collapse of their houses and shelters in the face of a Category 4’s catastrophic rage.

Meanwhile, the monumental weight of the Hurricane’s size and muscle pressed down on the coastal ocean surface, displacing the seawater and pushing it over Camagüey’s shore heavily, and persistently. From the notes of survivors, there was no tsunami, no ‘wall of water’, no sudden wave that swept through the city, as a generalized hurricane press releases can insinuate—in reality, the surge flowed in slowly, a gradual rise, but doing so with a terrifying progression.

We come back to the woman seeking refuge in her home—she hides in her bedroom, stunned at how powerful, and how deafening, the winds have suddenly become. They did not come and go like the straight-line gusts of traditional thunderstorms, but maintained their strength as a constant, ripping gale, screaming with excited terror. In nightmarish slow motion, the woman may have watched as opaque water began to trickle through the bottom of the front door and threshold—drizzling in at first, then accelerating to a steady pour. The saltwater sloshes to cover the floorboards of every room; without a second floor, the woman may have scurried on top of her bed or some other elevated piece of household family, maybe when the water was ankle deep, or maybe not until it had risen to her waist. She felt her world caving in around her, blurring the vision in the corners of her eyes with a watery demise—she could not tell if it was the rainwater pouring over her head from the cracks in the ceiling, or salty tears of fear.

The water rose higher, deeper, faster. It was filled with the sediment of dense debris clusters and miscellaneous pieces of strange rubbish that made the woman squirm when they brushed softly against her legs—bedded below the surface of the brown water… that, which was to be, the last thing she would ever see. She screams in sadness, in terror and in hopelessness; but her cries are drowned, absorbed, and amalgamated with those of the storm’s. She swims blindly in the dark, tries to break or cling to barriers desperately, but the palm of her hand slaps fruitlessly against stubborn vertical building components, teed against horizontal floating debris. And with air escaping the last confines of space between the rising sea and the ceiling, the woman succumbs to a victimhood that thousands others like her will face.

As Fourteen burst the Caribbean Sea from its banks, pushing harder and harder into Camagüey Province with the malevolent thrusting of her eastern eyewall, the low-lying coast that Santa Cruz del Sur called its home was completely buried by the ocean. By 9 am local time, the catastrophic tide had risen to 9 feet above normally dry ground within the town. Structures that had, up to that point, withstood the tearing maliciousness of 150 mph sustained winds, could not survive—nor resist—the rhythmic sledgehammer of ~10 foot high swells rolling in on top of the surge. Buildings crumpled feebly as if they were houses of cards—chewed, swallowed, and digested by Hurricane Fourteen’s ceaseless appetite for devastation.

The cataclysm came to an apex between 10-11 am on November 9th—right around when the Hurricane’s massive, 918 millibar eye would’ve been making landfall between the port of Santa María and Punta Macurijes, Cuba—it was then when the town of Santa Cruz del Sur became engulfed under an unimaginable 21.8 feet of seawater storm surge above normally high ground… and if taking in account the peak of the swells atop the surge, the measuring tape travelled 27-30 feet from the ground to the surface. The entire town faced complete and apocalyptic absorption into the Caribbean Sea, with the turbulent currents beneath the surface ripping, razing, and totally obliterating virtually every single building and structure of the town. The Hurricane’s eyewall didn’t stop there, continuing to push her Caribbean puppet soldiers further inland, penetrating more than ~12 miles into Camagüey’s interior. The scale, totality, and unsurvivability of the eyewall’s hellacious winds, and the unprecedented surge flooding with which it carried, is almost impossible to reasonably understand.

Fourteen pushed forward, cutting through the dead-center interior of Camagüey Province. The mammoth, 40-mile wide eyewall, having all but pulverized and leveled nearly the entire Province’s coastline, continued on as a harpoon of Category 4 zephyrs that lacerated the entire width of Cuba. Dozens of towns, farmlands, and forests experienced devastating wind damage as the core bulldozed over them; the city of Camagüey itself was among the areas to come under a direct hit, suffering severe and deadly desecration. The winds alone in these areas killed hundreds, tearing buildings apart and sending their skeletal remains on lethal trajectories through the air.

The Hurricane’s fiefdom of impacts was so wide, that port cities even as far away as Caibarién, which lies around ~155 miles to Santa Cruz del Sur’s northwest, reported significant storm surge flooding in their coastal districts (being to the west of Fourteen’s landfall, the direction of wind would’ve been to the south, accounting for the flooding along Cuba’s northern coast in addition to the major surge to the east of the storm’s landfall location).

Roughly ~6 hours after landfall, Fourteen completed her Cuban crossover, entering into the Atlantic as a low-end Category 4 spinner. She would make a few, final landfalls over the sparsely populated southeastern Bahamas as a degrading Major Hurricane before heading out to sea; there, she would very gradually weaken over the next five days, culminating in her ultimate death on November 14th, 1932.

When the 20+ foot floodwaters in Santa Cruz del Sur finally receded late in the evening of November 9th, after having covered the town so thoroughly as to make it appear as if there were never any town at all for several hours, the landscape was unrecognizable. And in the coming days, the bloody, grotesque reality would slowly creep out of the shadows for all to see.

It was a disaster, that the nation of Cuba would never forget.

Camagüey’s Catastrophe.

Nobody knows how the great “Cuba” Hurricane of 1932 was able to hold the intensity she did for so long in the month of November; nobody knows why the Cuban National Observatory refused to give any warnings to Camagüey Province (despite knowing that the storm was likely to make landfall in Cuba) until the cyclone was practically on top of them; and nobody knows how anyone survived the apocalyptic storm surge that wiped the town of Santa Cruz del Sur off the map. But a few did—and their accounts, testimonies, and horrifying, blood-curdling memories of that horrendous morning of November the 9th, 1932 is how we are able to write about this great catastrophe today.

The inland populaces, affected exclusively by the Hurricane’s winds alone, were the first to be reached by Cuban authorities in the aftermath of the catastrophic storm’s passing. This included the city of Camagüey itself, of which the eyewall had crossed directly over on the afternoon of November 9th. Across the municipality that the surrounding Province was named after, window coverings and infills were shattered, newly integrated electrical poles downed, and streets cluttered with torn roof debris and pulverized vegetation. Within the city and surrounding areas, the death toll was counted at 163, with most of the casualties being inflicted by falling trees and flying projectiles.

The epicenter of the storm’s landfall—Santa Cruz del Sur—however, would be totally inaccessible to outsiders for three full days, as the surrounding damage was so extreme, it had blocked off any viable entrances routes. The tedious, sweltering work of clearing them would be the only way in.

Cuba’s army corps was dispatched to assess the aftermath along Camagüey’s despoiled coastline, and they would be the first to reach whatever was left of Santa Cruz del Sur on November 12th. As the reports go, the assigned soldiers apparently pillaged the ransacked city, looting the flattened remnants of buildings and swiping valuables off the rotting corpses that were callously entangled with the rubble that stretched for miles around.

The first real aid did not reach Santa Cruz del Sur until November 19th—ten days after landfall—in the form of a single train carrying humanitarian supplies and hundreds of relief workers, some of which may have been volunteer.

When those people stepped out the doors of the train cars, into the tropical heat that seemed more sweltering than usual, they were met with a suffocating stench of such incredibly revolting abhorrence, grown men spilled their lunch on the spot. It was the smell of hundreds—no, thousands—of lifeless bodies, decaying stickily in the harsh, Cuban sun. The people walked forward with cloths over their faces, into the remains of the once-beautiful town, now razed to nothing but sharp, never-ending piles of broken wood, shattered roofs, and cleared foundations. The people clambered over the collapsed buildings numbly, refusing to believe the breadth of death and destruction their gazing eyes could not escape in any direction; and within the sickly whispers of the torn and tattered palm tress, an echo across a city reduced to rubble, the bilious ghost of the deadliest Hurricane in Cuba’s history defiantly remained.

The gruesome cleanup that ensued is almost too appalling to speak of: roving groups of men spread all over the ruins of the town, searching tiresomely for the dead and the buried. They would dig out thousands of decomposing corpses during the next several weeks, stacking their lifeless bodies in great, nauseating piles on the shores of Camagüey, where they would light them ablaze into massive bonfires of flesh and bone. The smoke from the fires (that seemed to be running non-stop for days on end) created an emetic, ghastly blanket of stomach-churning haze over the demolished town, eliciting an atmosphere of such traumatic, mind-scarring nature, it could only be trumped by the horrors of 20th century warfare.

Here… in this wasteland of unthinkable loss, grief, sorrow, and repulsiveness, even the buzzing flies feasting on carcasses, and zipping mosquitos reproducing in the orangish-brown puddles of putrid, standing water, seemed to sing quiet songs of tragedy. The power of the Hurricane’s oceanic push had disappeared all of Santa Cruz del Sur beneath the waves, leaving behind a hellscape where virtually every single manmade structure had been completely and totally reduced to its starting materials.

At the end of the counting, the burying, the burning, and the crumbling down to one’s knees, the death toll in Santa Cruz del Sur was confirmed to be that of 2,870 town residents—though the true number of casualties was likely much higher, when combining the countless bodies swept out to sea, never to be found, and the many dozens of survivors who’d been found alive buried in the town’s rubble, only to die days later in hospitals in Camagüey from either their injuries or the strain of the conditions they had to endure for ten days before the first help came (they did not tally their deaths as related to the Hurricane). In total, Cuba lost more than >3,033 lives to the merciless jaws of the great Hurricane, to go along with at least ~180 others throughout the Caymans, Bahamas, and South America. By a wide margin, it was the worst natural disaster in the island’s recorded history.

The extent of the catastrophe was a result of the many, historic factors that came together at just the right time to produce one of the all-time most severe tropical cyclones ever recorded in the Atlantic Basin. The intensity Hurricane Fourteen reached remains unprecedented in a storm during the month of November—since then, only 1 other storm, Hurricane Iota in 2020, has managed to force her central pressure below 920 millibars in this autumn timeframe—and Fourteen’s sheer size was also equally deranged, creating a gigantic expanse within which her radius of gale-force winds could collect the Caribbean Sea with the arms of her rainbands. And finally, it was the very slow northwest-to-northeast curve, at which Fourteen executed, while sustaining Category 5 winds longer than any other Atlantic Hurricane in history, that gave the storm a treacherous amount of time to accumulate storm surge beneath her. The angle of landfall, too, was perfect for a disaster, directing the strongest quadrant of Fourteen’s power, her eastern eyewall, straight into Santa Cruz del Sur. By coinciding with the hesitance from Cuban authorities, and the unalloyed lack of awareness from the rural communities in the Hurricane’s path as a result, Fourteen far surpassed even her wildest, most bestial dreams of human destruction, and loss.

A hole had struck at the heart of the people of Camagüey Province—and it was a hole, that would never truly be filled.

It’s November 9th, 2008—76 years to the day when the 1932 “Cuba” Hurricane had made landfall. The town of Santa Cruz del Sur had rebuilt since that day of endless horrors—that day of unparalleled tragedy, and disaster. They were a tranquil seaside village once again, enjoying the simple things of life in rural Cuba. They were far from the culture of Havana or most other cities on the island, having managed to resist becoming a tourist center, instead opting to maintain just a little bit of that true, Cuban Paradise of old.

But on this 76th Anniversary of the nation’s bloodiest day, another powerful storm was lurking just beyond the glittering horizon, borne from that same turquoise water that had conceived birth to Fourteen.

Hurricane Paloma, a virulent, 145 mph Category 4 at her peak, was fast approaching a direct landfall just to the west of Santa Cruz del Sur… and she was forecast to bring a similarly cataclysmic surge of 20-25 feet to southeastern Cuba… on the very same place, on the very same day, during the very same month, as the ‘32 tempest. This time, however, Ishmael’s seafaring warnings would not go unheeded.

Now, the lessons had been learned—the Cuban government, this time frantic, prompt, and deadly serious, evacuated an incredible 1.2 million people from the southeastern coast of the country, accounting for over 10% of the nation’s entire population.

In the end, these drastic measures turned out to be largely overdone, as Paloma would collapse radically in her final hours before landfall, striking Santa Cruz del Sur as an unravelling 100 mph Category 2 Hurricane. Because of the prompt and massive relocation effort, only 1 fatality was recorded to be directly caused by Paloma’s impact—so perhaps she was just a playfully sadistic gagster, hoping only to hoax the Cuban people into reacting the way they did, just for her to innocently waddle ashore, laughing hysterically at her own exploits. But however cruel or silly Paloma’s intentions were, she nevertheless exposed the extent of how little the scar, carved by the ‘32 Hurricane in the hearts and minds of the Cuban people, had truly, fully healed…

Because the story of an unsuspecting city, who’d found themselves caught in the furious rampage of a storm without limits… the story of a city, that was once wiped off the very face of this Earth… will never be forgotten.